David Larter over at Navy Times has an interesting story up, detailing the average time Navy combatants have spent at sea over the past three years.

David Larter over at Navy Times has an interesting story up, detailing the average time Navy combatants have spent at sea over the past three years.

Go take a look. The data, apparently acquired from the Center for Naval Analyses, is good stuff–you can break it down to the individual ship level for almost every ship class in the Navy.

But according to Mr. Larter, “officials were unable to release similar data for coastal patrol ships, mine countermeasures ships, logistics ships or submarine tenders.”

Wait, really?

Despite the fact that Mr. Larter is a dedicated Navy reporter, and his data apparently came from CNA, a dedicated Navy thinktank, AND Mr. Larter’s request was likely vetted through several Navy PAOs, surely somebody, somewhere, would know the Navy released data on logistics ships and sub tenders here, here and here?

I’m stunned.

The information our intrepid Mr. Larter needed was open for anybody to read in something called the Military Sealift Command’s Annual Report (Go take a look–it’s a really well-done 20,000ft summary–a must-have for Congressional staffers), under the handy charts entitled “Operating Tempo”.

There’s a lot of neat data in there for Mr. Larter to ponder.

Take Mr. Larter’s key takeaway–that the Fleet is at sea 33% of the time.

Well, MSC would love to be at sea only 33% of the time.

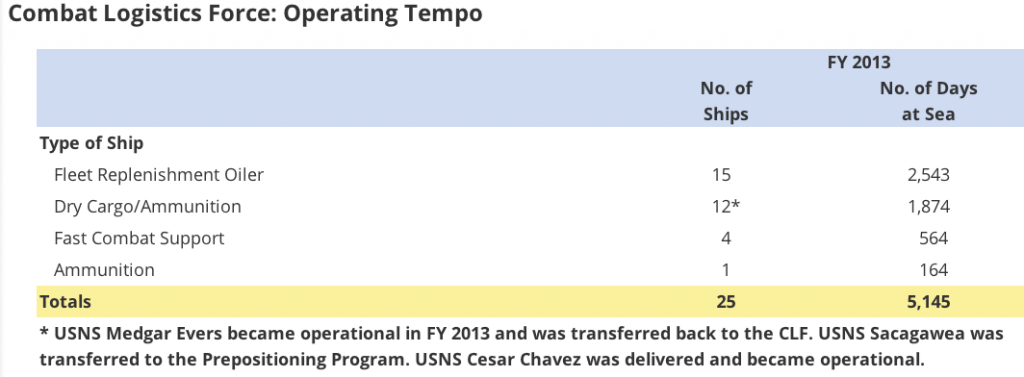

The CIVMAR crews run these ships–they get ’em out and keep ’em out. Take a look at the CLF–Over the course of FY 13, fifteen middle-aged Kaiser Class T-AOs spent 2,543 days at sea. That’s 46% of the time. Amazing, huh? The Lewis and Clark T-AKE’s were at sea 43% of the time. The fast T-AOEs were at sea 39% of the year.

Here’s the breakdown:

And that robust operating tempo chalked up by the CLF? Why, in several select corners of the MSC Fleet, some ships are far more active than the already hard-pressed CLF. MSC’s six oceanographic survey ships were at sea an eye-popping 71% of the time in FY 2013 (T-AGS hulls). The five MSC ocean surveillance ships (the T-AGOS hulls) were at sea 64% of the time. Even the USNS Ponce–the model for the Afloat Forward Staging Bases–was at sea 47% of the fiscal year (while her USN sister ship USS Denver was only at sea 32% of the time).

So I think there is an obvious reason here as to why the Navy was reluctant to suggest Mr. Larter compare the Navy’s performance with MSC’s published figures. The good ole MSC CIVMARS simply outperformed their Navy brethren.

So I think there is an obvious reason here as to why the Navy was reluctant to suggest Mr. Larter compare the Navy’s performance with MSC’s published figures. The good ole MSC CIVMARS simply outperformed their Navy brethren.

That operational disparity is not something the Navy is eager to discuss. One might even think the Old School Navy is starting to feel threatened by the MSC’s consistent performance year-after-year-after-year.

They should.

The MSC is doing great with what little they have, and, frankly, I think it is a shame that most everyone in Big Navy (most everyone besides the CNO) is out there sorta treating the MSC with distain. Seems like the Navy might be able to learn a thing or two from these MSC guys. (my prior thoughts on the matter are available here), and, frankly, when the JHSV, MLP and AFSBs enter the fleet, the operational disparity between America’s first and third biggest navies will only increase.

MSC aside, Mr. Larter, in his reporting, overlooked a few newsworthy gems hidden away in his data.

Some are worth quickly discussing:

First is that the LPD-17 class seems to have put their sailing problems behind ’em. A few years ago, I personally would have never expected to see USS San Antonio (LPD-17) sporting a 40% underway time. It’s good to see this program actually starting to perform.

Also, I’m still a bit shocked that LCS-2, the USS Independence, has reportedly been underway less than 20% of the time over the last three years, and that USS Freedom, LCS-1, with a reputation of being something of a shipyard queen, was apparently underway about 60% 22% of the time (Apologies–if you dig into the numbers, it looks like somebody transposed the Enterprise’s underway percentage to LCS-1. The more realistic number is in the chart of individual ships). I’m still scratching my head on how those sets of statistics were developed, but Lockheed has got to be enjoying the publication of this information now, just as the Small Surface Combatant evaluators are writing up their recommendations.

{ 5 comments… read them below or add one }

MSC ships are used to show the flag today out in 7th Fleet. MSC routinely sends ships for maintenance in Vietnam to win hearts and minds (and hopefully open another possible maintenance hub in time of crisis). Also, the Junk boats (ARS and ATF platforms with embarked military divers) are also sometimes the only ships that make it to CARAT, JPAC, or other TSC engagements.

Great comments you folks…

Mark, just a few peripheral, off-the-cuff comments–no offense meant to the USN. I’m just trying to raise the MSC’s profile. And I think that, for MSC CLF assets, sea-time is an entirely appropriate evaluation–it shows that these assets, in peacetime, are being heavily used…which leads to the question of sufficiency. Do we have enough hulls to manage CLF demands in a contested ocean?

Regarding forward basing and port calls…Is a port attack really an attack on two nations? Hmm….I don’t think the Cole attack was seen as an attack on two nations. It was pretty clearly targeted on a single nation…Also, an attack just outside the neutral harbor entrance is a time-honored tradition.

I’m only looking at sea time, yes. Evaluating influence is something else entirely. That said, I’d posit that MSC port call visits would hold a significant impact if they were done more often. Heck, Chile was still buzzing about some crazy MSC-manned catamaran that dropped by YEARS AFTER it came through. I agree with you that the primary CLF mission is to enable power projection assets, but, frankly, I think all the CLF vessels should have the capability (fly-in teams or whatever) to be used to support a wider mission set–port visits and shore engagements…and a few other influence-enhancing activities too.

I agree that the disparity does not reflect poorly on the combatant USN, but I believe that Craig is attempting to elevate the visibility of MSC across the Defense Department and the Navy.

With the transfer of USS Frank Cable on Feb. 1, 2010, all Navy auxiliary vessels fall under the administrative control of MSC, with either merchant marine crews (civilian or contract mariners) or hybrid civilian/naval personnel on board. As this role has expanded, those with the experience of underway and vertical replenishment no longer resides in the active duty Navy, but with the civilians of MSC.

I do disagree with your statement that MSC has fewer maintenance requirements and can play while “hurt”. Ships like the T-AOs not only have to meet USN standards and practices, but also American Bureau of Shipping. This necessitates an extensive level of upkeep and periodic drydocking and inspection. While MSC ship do not have extensive weapons systems – they do possess a different level of main armament; cargo pumps on oilers, helicopters, elevators, cargo rigs, and engines that lack many of the redundancies on board naval combatants.

The pay and morale issues are a tough one to compare as civilian mariners are paid better but their work and leave schedules are terrible compared to the military. Plus the only billets for mariners are on board ship, while sailors rotate between ship and shore assignments.

I think all of these points are great ones and need to be raised as it elevates the discourse on the role that MSC and merchant mariners play in the national defense of our nation.

Seems like I’m too often weighing in as a critic here, but I find nothing about this days-underway disparity to necessarily reflect well on MSC or poorly on the combatant USN. Consider:

1. Assuming peacetime forward deployment, there is little difference whether the combatant is underway or visiting a foreign base or port. The long transit across the Atlantic/Med or Pacific is accomplished and its overseas presence is established, at sea or not. Indeed, a combatant visible in port is sometimes contributing more to regional stability than while at sea. Is it necessarily more vulnerable in port? Attacking it in a foreign port requires attacking TWO nations – a daunting proposition. Replenishment vessels don’t have either the luxury or same impact in port. Their job is to maintain combatant presence.

2. Replenishment inherently requires distant steaming and long days because the most needy combatants are far from home shores. A combatant performing brief near-home training cruises doesn’t need UnRep, so MSC vessels are always ‘over there.’

3. MSC vessels have fewer maintenance requirements and can ‘play while hurt.’ They can deliver with a broken radar, half their equipment deadlined and no complex armaments to maintain. And replenishment concepts haven’t really changed since VirtRep was introduced. Combatants don’t have this low-tech luxury (sorry). And unlike CVNs and subs, MSC ships don’t spend three years laid up for reactor refuelings. Calling one ship merely a delivery truck and the other a Formula One racer is exaggerating, I admit, but which one has more tech requiring more in-port upgrades, tuning and maintenance?

4. Pay and morale issues. CivMars are paid more than enlisteds, partly due to the expected time at sea. Also, the larger replenishment ships are not as hellish in high seas as frigates, destroyers and cruisers. Those 45-degree roles in combatants warrant 45 days of liberty.

So the First and Third Navies are materially, operationally and culturally different animals. For similar reasons, USAF transport crews have more flight hours than TacAir jocks. The MSCs long periods underway are by design, not due to inspired or enlightened management.

Craig,

The numbers you found do make for an interesting comparison. I think the Navy could benefit from examining some of the CIVMAR crew management practices. During my own limited exposure, I observed that a portion of the CIVMAR crew rotated out about every 3-4 months. The outgoing professional mariner had a small turnover with the incoming. Only a portion of the crew swapped out at any one time and generally it was the same people rotating in/out. I think a fractional crew rotation policy could work better for the Navy than the current concept of swapping an entire crew at one time. The COD or port calls could be used to facilitate the swaps. Fractional rotations could ameliorate some of the crew fatigue concerns expressed in the Navy Times article while increasing the grey hull underway times. That coupled with more forward basing and less time spent in transit could help mitigate declining hull numbers. Fractional crew rotations would probably require an increase in the training level and changes to the way ships qualify watchstanders so that the outgoing crew member is not replaced with a novice that spends most of their rotation qualifying.