I published a commentary over at DefenseOne.com last week, suggesting that the Navy commission a new public shipyard. You can read it here, but the general gist is this:

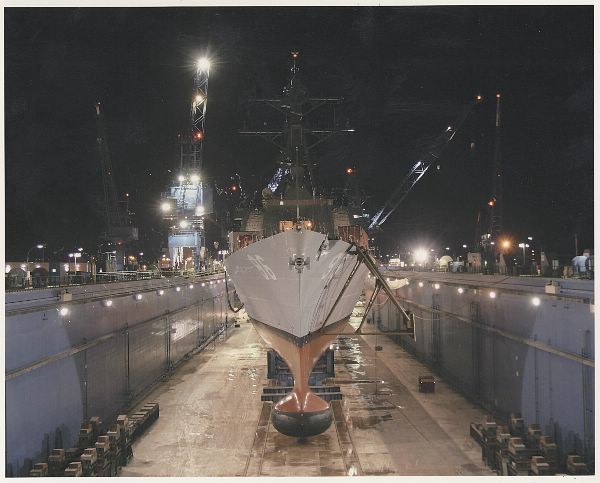

The U.S. Navy’s four public shipyards are overwhelmed. Budget documents show that their workload exceeds their capacity by 117 to 153 percent — that is, there’s too much to get done and too few dry docks to do it. And despite reams of studies detailing the Navy’s maintenance challenges, official Washington is overlooking the obvious solution: open a new national shipyard.

Now, this DefenseOne.com post went live in the midst of the Annual Surface Navy Association meeting, so I had a few lively discussions with stakeholders that merit additional discussion.

The Public Has Forgotten Why Public Shipyards Exist:

First, after chatting with several stakeholders, I worry that America has forgotten why public shipyards exist.

In my mind, public shipyards exist to prepare the Fleet for battle. By being taxpayer owned, they provide the Navy with the flexibility to address casualties and battle damage in prompt fashion, and sometimes (when they are located in strategically useful areas) offer the Navy opportunities to operate forward, nearer to trouble.

Public shipyards also support shipbuilding/ship repair in regions and mission activities (like, say nuclear powerplant repair) where private industry is unable/unwilling to develop a viable business case–serving, in some places, as a maritime industry incubator. That’s why the public shipyards focus, today, on decommissioning and repairing nuclear vessels and subs.

This has all been forgotten. But what really worries me is that too many naval stakeholders have forgotten that National shipyards are necessary to back a truly globally-challenged Navy. The last real, honest-to-goodness maritime rival America has confronted was retired in the 1940’s, and we needed twelve public yards to do it. The Russians, as scary as they might have been, were, at best, regional operators—barely capable of causing real trouble beyond their SSBN bastions or, on rare occasions, the Mediterranean.

A globe-spanning rival Navy is something modern “mechanized” America has only grappled with for a relatively few years and long ago–between the Spanish American War and the Second World War, when we jostled uneasily with growing British, German and Japanese fleets. Contested seas need ready, well-maintained ships.

Naval stakeholders have forgotten that National Shipyards help address the intense operational and maintenance demands global maritime rivalries place upon Navies. Navy vessels need to be operationally ready for war (with systems sustained at a far higher level than we are used to), the ships will need to look good to help keep the Allies excited and engaged, and, frankly, in the competitive atmosphere of the next few decades, naval vessels going to get used hard in ways current Operations and Maintenance models do not anticipate.

America has also forgotten that National Shipyards, in a period where repair timelines will be compressed, save both time and money. The days where NAVSEA and industry contracts specialists can spend sixteen months leisurely bickering over work packages for a six-month ship alteration are almost over. Timelines are only going to get shorter. Expect intensive pressure to find, fix and finish maintenance problems; and while Private yards can certainly do this, they’ll bleed the Navy dry doing it unless there’s an alternative path or competition (Not casting aspersion here. It’s just what any private business would do given similar circumstances).

In short, if we’re going to need another yard (or even keep the ones we have), the Navy must do a better job of defining National Shipyards and explaining their critical role in maritime security.

Change the Narrative:

But better defining the role of National Shipyards in national security is hard because shipbuilding has an image problem. Nobody raises their kids to be shipyard workers anymore. The entire profession is wrongly perceived as a dirty, dangerous profession for deadbeats. And yeah, while it may not be a quick route to cushy office work, it is full of challenges that reward intelligence and drive—probably more directly than many basic Ph.D. opportunities. The industry may be rough-hewn but it is full of smart people–I mean, I still remember my first sit-down with Huntington Ingalls folks, and going “my god, these guys are geniuses”.

So while shipbuilding has an image problem, the National Yards bear the brunt of it. These yards have been gleefully beaten down by Congress and other maritime stakeholders to the point where they’re perceived to be the worst remaining parts of a bad, old-tech industry. It’s to the point where nobody but their hometown members of Congress will really fight for these critical facilities anymore. Industry lobbyists–who want to make the public yards go away–make it far too easy for politicians to dismiss these facilities as fatally troubled memorials of a dysfunctional and dated industry. And nobody is out there defending them. Any argument about National Shipyards is less about their critical contributions to national defense than a constant drum-beat of negative news detailing bad estimates, cost-and-schedule overruns, overhead and the occasional “let’s set fire to this sub so I can leave early” idiocy.

But the yards are better than the narrative makes them look. They’ve been starved of funding for a long time. And even on a shoestring budget and in crumbling facilities, Public Shipyard workers do amazingly innovative stuff, often in really tough conditions. This struggle doesn’t get recognized. But the Navy could, with a little creativity and effort, recast the way the National Shipyards are perceived by both the Public and Congress. A change in image would be enormously helpful in advancing the National case for National Shipyards. In contrast to all the lobbyists fighting for private shipyards, the Navy is the only advocate national shipyards have.

Rather than be presented as the last tired industrial monuments to an old way of doing things, the four remaining National Yards could the presented as the high-tech showpieces of tomorrow’s technology. A good rebranding would do these facilities an enormous amount of good.

That’s why I call the shipyards “National Shipyards” rather than public shipyards. The term “Public Shipyards” encapsulate every single possible bias in our high-tech, anti-public sector public has been sensitized to. Instead, the remaining national yards should be portrayed as cost-saving national investments that are incubators of new things rather than sustainers of old tech. Now…That’s a hard sell when a large part of National Shipyard business is maintaining creaky thirty-year old platforms (and, well, decommissioning ’em too), but new hulls and new platforms are coming (Virginias, Fords and Columbias), and the National Shipyards will be some of the first to grapple with their new technology. That is an opportunity the Navy would do well to grasp.

So, in my article, I suggested adding capacity (a new yard) and adapting a mission-oriented management model akin to the DOE’s high-tech national laboratories (where a quasi-private consortium handles management but the government owns the facilities and sets goals). That raised a few questions amongst skeptical stakeholders. But why not build or try an convert one of our national shipyards into a national laboratory-like equivalent, where the workers carry out the routine and needed vessel maintenance, but are also more tightly integrated into the wild cutting-edge stuff that is going on behind various doors at places like Battelle, Boeing or some other non-traditional maritime stakeholders. Just like the labs, National Shipyards could develop centers of government-funded equipment expertise–systems engineering, electronic warfare, unmanned, undersea, you name it.

Folks scoffed about looking beyond the traditional yards for operational expertise–it’d be hard for a contract officer to justify operators that work in a different field. Sure, Huntington Ingalls, General Dynamics and other yards offer production expertise. But….can they offer as an integrated portfolio of research activities as some of these non-traditional institutions? I mean, just look at what Battelle has going on in its maritime portfolio—wild stuff with high-density energy and small nuclear power-plants, lifecycle engineering, boutique artisanal sensors, subs, unmanned operational systems and so forth. There is a lot of high-tech, fascinating stuff getting into the maritime that could really benefit from having access to a Government yard focused on high-end support and GFE development/integration.

By adding some large research-and-management oriented Federally-Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) into the mix, the Navy–and Congress–gets a fascinating conglomeration of the best of both the public and private sectors. I could quite easily see one of our big FFRDCs taking over operations at, say, an existing private yard, and managing the facility quite easily.

In my mind, by getting another high-tech player into the game, the Navy also gets a another chance to change the narrative at the National Yards, shifting the shipyards from being perceived as just a crusty obstruction to private sector mission appropriation into something else—an arena for far more interesting and important endeavors.

Conclusion:

This isn’t everything. I have much more to say about National Yards, labor recruitment and training, facility building and commissioning timelines and America’s strange inability to build nuclear vessel-ready floating dry docks…plus a few other things, but all that is for a later post.

The bottom line is this: America can commission a new National Yard. The workload and mission-space demands it. Now that is no easy task….But America must also recognize that a new National Yard can (in this environment) be commissioned far more quickly than most traditional stakeholders believe. Creative application of available resources and savvy utilization of transient political opportunities can do a lot more–and a whole lot faster–than most of our stakeholders believe possible.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

In part 2, hope you briefly list and describe each of the National Shipyards.