Despite some recent balance sheet successes from Navy Shipbuilder Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) and a one-year reprieve on downsizing the nuclear carrier fleet, the company’s mid-term prospects are very worrisome.

Despite some recent balance sheet successes from Navy Shipbuilder Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) and a one-year reprieve on downsizing the nuclear carrier fleet, the company’s mid-term prospects are very worrisome.

This opinion stands as something of a contrarian view. And it certainly disagrees with Wall Street–after HII peeled away from Northrop Grumman in early 2011, HII stock has been on a tear, racing from a 2011 low towards triple-digit territory today. To HII’s credit, HII managers have been busy hunting for efficiencies, building a younger (and less costly) workforce, and working to maintain profits even in the face of dramatic cost-overruns. By some short-term balance sheet metrics, HII has been a smashing success.

But these successes could evaporate quickly. The harsh truth is that efficiency only works when a company actually has a quantity of work to optimize. And in the near to mid-term, the defense budget crunch may make a lot of HII’s work disappear.

Making matters worse, HII’s product pipeline is starting to look dangerously weak at a time when HII’s primary competitor, General Dynamics, is looking particularly strong and aggressive–if not dominant.

Of course, all is not lost. The HII stock climb offers HII both an opportunity and a challenge. A solid, growing stock price gives HII breathing room to change. But it also may fuel arguments for status quo, and enable HII to hold the current course longer than it should.

That would be a disaster.

To survive over the lean near-to-mid term, HII must get far leaner and far meaner. The transition from a relatively decorous and stodgy business of managing a safe half of the old General Dynamics/Northrop Grumman naval shipbuilding duopoly, well-protected by powerful Congressional Delegations (Remember how Mississippi Senator Trent Lott and Representative Gene Taylor did so well by HII?) to a far more competitive–and diversified–enterprise is going to be hard.

It remains to be seen if HII can muster the competitive and creative vision to carry it out. To help, I offer HII leadership a set of challenges and some solutions.

Here are the problems:

Problems in the Portfolio: An overarching problem with Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) is that virtually every single product HII yards manufacture (or propose to make) cannibalizes another of their products.

Problems in the Portfolio: An overarching problem with Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII) is that virtually every single product HII yards manufacture (or propose to make) cannibalizes another of their products.

Now, for those unfamiliar with this company, HII makes submarines (SSNs), nuclear carriers (CVNs), big-deck amphibs (LHA/LHDs), traditional amphibs (LPDs/LSDs), destroyers (DDGs) and National Security Cutters.

Here are some examples of the problem–If, for example, HII pushes to build more small carriers (LHA/LHDs), somebody wise at DOD will suggest slowing the CVN build-rate. Conversely, faster procurement of big carriers will eat away at arguments justifying more smaller amphibious carriers.

On the Amphib side of the house, should HII urge procurement of more LPD-17-like hulls, then that initiative might well risk a reduction in the overall pot of cash for Amphibious vessel recapitalization that might otherwise go to LHA/LHDs.

Even HII’s failed Offshore Patrol Cutter (OPC) proposal ate into the National Security Cutter’s business case.

Subs are HII’s only “safe” products. But, even then, with General Dynamics running the submarine collaboration/workshare business, I can’t see General Dynamics hesitating to sacrifice HII’s LSD business to help secure SSBN(X) funding (LSD recapitalization–LX(R) or LSD(X)– now sits right smack dab in the midst of the SSBN(X) build-out in the long-term shipbuilding plan).

Unless something changes in a fundamental, structural way, HII cannot win.

Compared to General Dynamics–where, I suspect, an enormous amount of attention has gone into creating non-overlapping product lines at each of the 3 General Dynamics shipyards–Huntington Ingalls has quite a task before it should the company seek to similarly deconflict their product lines.

Business Structure: A second problem is that HHI is, essentially, a single-product defense contractor, with little in the way of diversification. They build ships for Navy service. And that’s about it.

Business Structure: A second problem is that HHI is, essentially, a single-product defense contractor, with little in the way of diversification. They build ships for Navy service. And that’s about it.

HII’s inability to leverage a civilian market (in any sector) to ride out hiccups in the defense market is a serious vulnerability. General Dynamics has Gulfstream, Defense Conglomerate ATK has a thriving outdoorsman and civilian ammo business–even Lockheed is pressing ahead with civil ventures.

HII has lagged behind, only recently buying a nuclear industry cleanup concern, SM Stoller–which–don’t get me wrong–is a good idea.

But HII’s leisurely effort to diversify (a stab at power industry here, a poke into civilian shipbuilding there), coupled with an apparent inability to attract significant civilian shipbuilding customers in their naval yards, is a real concern.

Also, as naval platforms are rapidly becoming subordinate to payloads, the inability of HII to leverage a set relatively “in-house” business units to build some sort of integrated market (GD shipbuilders can easily turn to GDAIS or GDIT or even GD Land Systems for a wealth of in-house systems or in-depth knowledge of cutting-edge defense solutions, while HII–stripped of Northrop Grumman’s corporate support–has no such option.

These days, non-diversified shipyards that lack indigenous corporate payload integration and support resources are operating at a real disadvantage.

Numbers Games: Huntington Ingalls has, for too long, relied upon blanket appeals to “industrial base” preservation that centered upon inflated Cold War-esque “fleet size” requirements to market their products.

Numbers Games: Huntington Ingalls has, for too long, relied upon blanket appeals to “industrial base” preservation that centered upon inflated Cold War-esque “fleet size” requirements to market their products.

Marketing of Huntington Ingalls’ largest product lines–the CVNs and ships for the Amphibious force–have centered around a relatively easy argument-a national “need” to maintain a certain minimal number of ships–11ish CVNs, and 38 to 33-ish or so Amphibs. That’s a problem.

First, it puts the company in the position of defending an outdated Cold War-ish requirement.

Second, it’s perilous to make industrial base needs and fleet size requirements indistinguishable from one another. Such a tight link is more befitting a company backed by super-strong support from a Congress who could simply cite “industrial base” and shove HII products into the budget. That era (as least for HII) has passed.

Third, with essentially two amphibious ship lines (LPD and LHA/LHD) and a fixed amphibious fleet size, every Amphib that gets made aversely impacts the other.

Fourth, when a fleet requirement is defined, that number becomes, frankly, far easier to cut than to grow. The opportunity to grow the fleet is well worth the cost of insecurity/ambiguity.

And finally, a focus on numbers limits HII’s ability to respond to new situations. Fighting for a 38 to 33-ish Amphib fleet, when combined with HII’s rigid focus on fielding 11 CVNs, has inevitably limited HII’s willingness to channel resources into proposing new solutions for the non-Cold War world.

In contrast, General Dynamics has been an idea-incubator, refreshing their existing Cold War shipbuilding portfolio (DDG-51s, SSNs, SSBNs), and pushing ahead with new models like T-AKE, LCS (before getting sidelined as the acquisition model changed), the MLP/AFSB, and DDG-1000. And, once those new programs were underway, General Dynamics “works the refs” to grow the original requirement (often to HII’s detriment).

And now that HII is no longer the nation’s sole source of amphibious ships, HII’s no-holds-barred effort to keep the Amphib fleet at a certain size has backfired, and simply facilitated an easy entry for General Dynamics to sweep in and round out the aging amphibious fleet with their low-cost MLP/AFSB platforms.

Trapped in Partnership: Back when shipbuilding “partnerships” were in vogue, Northrop Grumman forced the future Huntington Ingalls (HII) to go “all in”, partnering with General Dynamics (GD) in sub-building, DDG-1000, and DDG-51 work.

Trapped in Partnership: Back when shipbuilding “partnerships” were in vogue, Northrop Grumman forced the future Huntington Ingalls (HII) to go “all in”, partnering with General Dynamics (GD) in sub-building, DDG-1000, and DDG-51 work.

Partnering hasn’t worked out well for HII. As far as surface ships go, GD has underbid HII on DDGs, stolen away the DDG-1000 business, and, in the undersea domain, GD has really marginalized the perception of HII’s ability to contribute to next-generation subs.

Now, I certainly don’t know the details of the HII/GD teaming or workshare agreements, but I’ll bet that in their eagerness to maintain their LPD-17 and DDG-51 business, HII is effectively trapped into really tough terms, and left unable to pursue projects that might stand a chance of impacting DDG-1000 and SSN/SSBN product lines. Partnering certainly earned HII some short-term wins, but it may not have been worth the long-term cost.

Partnerships were originally pursued to preserve industrial base. But, today, preservation of the industrial base is taking a back seat to lowest cost, and HII simply hasn’t been able to respond quickly enough. HII has had to shutter their Avondale, close a cutting-edge composite yard, and, by the end of this sequestration business, it may well loose more.

Trapped By Payload: If we take the view that payloads are starting to matter more than platforms, then HII has a real problem. Virtually every single marquee platform they build is beset with marquee payload issues.

Trapped By Payload: If we take the view that payloads are starting to matter more than platforms, then HII has a real problem. Virtually every single marquee platform they build is beset with marquee payload issues.

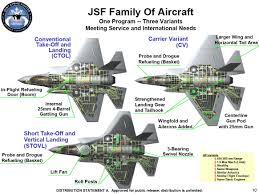

Challenges with F-35 B and C are impacting the CVN and LHA/LHD business case.

The perennial and ever-failing Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle/Amphibious tractor impacts the LHA/LHD/LPD lines.

It all leads to a question…If the primary payloads used for the platforms are unworkable and unaffordable, then, again, why build the platform?

HII has failed to force the primary payload contractors to be actively engaged in helping their platform sold in Washington. But, then again, if the contractor for a troubled primary payload is busy fighting to keep their program alive, they’re not going to be in a position to support HII ships (It just gets too ugly–A 20-F-35B loadout of an LHA costs–in the best case–about 2/3 of the ship procurement expense. Worst case, the payload will cost more than the ship itself. What options does a naval shipbuilder have when the payload costs more than the platform?)

Rather than support their host platform, payload contractors are certainly enjoying their new importance, and seem quite eager to shift all the risk they can onto the shipbuilder, only to stand aside and shrug when integration issues start popping up and hindering platform performance.

The competitive position gets far bleaker as older marquee payloads end production. HII’s ongoing CVN marketing push could have really benefitted from leveraging the marketing might of Boeing in their struggle to keep the F-18 production line hot. But that option is now closed. When the primary things that come off a carrier or LPD-17 or LHA/LHD are no longer in production, the relevant pro-CVN/pro-Amphib supplier base contracts enormously.

Don’t believe me? Then go sit in on the Lockheed Littoral Combat Ship Industry Day–the secret sauce for Lockheed is that they celebrate manufacturers of the payloads/systems coming off the LCS (many of which are, naturally, made by Lockheed Martin) more than the ship itself.

In contrast–and while General Dynamics’ marquee platforms don’t yield an inch on future “whiz-bang” capability, the have a solid foundation on mature and “in-production” payloads–DDG/DDG-1000 rely on Standard Missiles, the T-AKE disburses food, fuel and ammo, the SSBN carries Trident IIs and fancy warheads, and the SSN offers Tomahawks and some other interesting items.

Well-known and politically well-supported, popular payloads are the foundation of the General Dynamics-built ships, and while innovation is highlighted in the press, in reality, that innovation is largely kept to the fringes of the central product.

Trapped by low-end: By doubling down on the defense of high-end capability, HII has totally misplayed the emergence of low-end platforms, and is now in a terrible position as procurement begins to fix upon those low-cost solutions.

Trapped by low-end: By doubling down on the defense of high-end capability, HII has totally misplayed the emergence of low-end platforms, and is now in a terrible position as procurement begins to fix upon those low-cost solutions.

The failure to tend the low-end is a critical oversight–and it opened a niche that General Dynamics has happily filled.

Take the cost-effective Mobile Landing Platform (MLP)–the General Dynamics-built MLP and its big-deck relative, the Afloat Forward Staging Base (AFSB), are going to be gunning for the LS(X) contract. The MLP/AFSB duo are the perfect low-end amphib, providing an 80% solution for a fraction of the conventional LPD/LSD/LHA/LHD cost. (And by pushing to move the LS(X) procurement into the 2020s, just as the pricey SSBN(X) is procured, the Navy won’t have any money to buy anything else but modified MLPs.)

I offer HII Leadership a few suggestions–some obvious and already being dealt with, and others that are somewhat less so. Here’s the list:

1. Continue driving efficiencies and improving quality: If HII can’t compete on price, then it can’t compete. Naval leaders may pay lip service to “preserving the industrial base”, but, really, competitive cost shoot-outs are the future.

2. Diversify: Efforts to diversify must accelerate, and it probably is easiest to absorb any resulting start-up/merger costs when the HII stock price is not under downward pressure. To survive, revenue from civilian business lines–in shipbuilding, energy or some other completely different business–might be very helpful in the years ahead.

3. Disassociate product lines: Stop the conventional and big-deck amphibs from eating one another. The Pro-LPD-17 “How Many Ships Can One Ship Be” campaign was a good start, but halfhearted. In that campaign, the LPD-17 was an amphib, when maybe, for competitive reasons, it should be reinvented as a cost-conscious large surface combatant, or (with the Ticos going away) a next-gen CG(X), a DDG-1000 competitor or even a Prompt Global Strike platform. The next thing that needs doing is an effort to differentiate between big-deck amphibs and big-deck carriers. And finally, HII needs to tap some creative resources and design a few new things to fill unmet Navy needs.

4. Compete directly: Realize the days of a healthy duopoly are over. General Dynamics is your competitor, and it makes no sense to pretend they don’t exist as a competitive and existential threat. Go. After. Them. Start a whisper campaign about DDG-1000 manning (How is the tiny DDG-1000 crew going to handle vast battle management responsibilities and fight their ship with a compliment that barely tops the upsized LCS crew?). Make a DDG-1000 alternative from an LPD-17 hull that is cheaper than the existing Zumwalt hullform and, if you can, directly–and publicly–compete (this dumb video won’t cut it). Start asking pointed questions about the shock-hardening of the LPD-17 hull versus the lack of survivability of a civilianized MLP.

4. Compete directly: Realize the days of a healthy duopoly are over. General Dynamics is your competitor, and it makes no sense to pretend they don’t exist as a competitive and existential threat. Go. After. Them. Start a whisper campaign about DDG-1000 manning (How is the tiny DDG-1000 crew going to handle vast battle management responsibilities and fight their ship with a compliment that barely tops the upsized LCS crew?). Make a DDG-1000 alternative from an LPD-17 hull that is cheaper than the existing Zumwalt hullform and, if you can, directly–and publicly–compete (this dumb video won’t cut it). Start asking pointed questions about the shock-hardening of the LPD-17 hull versus the lack of survivability of a civilianized MLP.

5. Establish A “Low-End Solutions” Department: Move quickly to provide a competitive alternative to the MLP and AFSB by developing low-end, civil-spec amphibs. And then, to start owning the low-end sub business, get into conventional subs/UUVs in a major way (hell, start setting up to partner with Japan when that country opens up).

6. Build upon HII’s energy-generation/atomic energy management strengths: HII is the king of ship-borne nuclear power systems. If energy is gong to power the weapons of the future, then go retro and start presenting nuclear-powered surface combatants and making the case for them. The fleet will be recapitalizing the oiler fleet soon, so while competing there for T-AO(X)s, start re-invigorating the fiscal case for nuclear surface combatants.

7. Stop being last: Defending status quo has been a way of life for too long at HII, and they need to get creative in capturing the initiative. Look at HII’s high-profile (and pricey) start of the Amphibious Warship Industrial Base Coalition. To me, it’s a thinly-veiled attempt to restart the ineffective and failed American Shipbuilding Association, and merely mimics what the Sub and Littoral Combat Ship community have been doing for years. If HII is the leader of the naval shipbuilding industry, then HII needs to lead the pack rather than follow.

8. Promote the next Cold War: Look, I hate being a war-monger, but HII builds things for grand-scale Cold War, State-on-State conflicts…so if HII isn’t pushing (and funding) those organizations that might be in the business of promoting a return to Cold War conditions, then HII is loosing an opportunity. HII needs to start having Congressmen like Randy Forbes, or the well-paid defense mouthpiece Loren Thompson or some other thinktanks out there actively wondering, in a very pubic fashion, just how the US will project power in the Indo-Pacific Ocean when bases like Diego Garcia go away. Or how the U.S. will provide air cover once China has a brace of carriers.

9. Get Payload People to Pitch In: HII is building platforms for payloads. At a minimum, the suppliers who build those payloads need to work for HII in promoting HII platforms–and it’s only right to do so, given that HII suffers real risks if the payloads go off-schedule or become hard-to-integrate nightmares. Supplier organizations are not just about the folks who supply ship stuff–the ship engines, the captain’s chair, the seal on the fourth bulkhead and so forth. Platform advocates should encompass the “mission” packages as well, and an effort should be made to get platform associated with well-performing payloads programs. (And, frankly, I think there is room for tweaking the business model a bit to help compensate for the shipbuilder’s increasing subordination to payload providers…but I’m still mulling just how to do that.)

10. Stop Being a Sinecure for Retired Officers: Retired officers are great at opening doors, but they come weighted with years and years of pre-conditioning that makes many of them prone to groupthink. Or they enter industry with idea that, while in the industry club, one should be decorous and never, um, get too aggressive in fighting for a product (My motto is that no contractor can do very wrong if he places his product alongside that of the competitor!) or working to change the direction of the “customer”.

If HII wants creativity or combativeness, hire outside of that group, or, at least, switch it up. Putting, say, a retired USMC general officer in charge of the Flight II LPD-17 project will do nothing to help LPD-17 grow beyond it’s amphibious roots. HII doesn’t really need a USMC guy to market an amphib to the Marine Corps–they want hulls, and they’ll go support anything they can get. HII should put somebody else in charge–or stick with USN(Retired) but try putting a missile-defense Cruiser-Destroyer guy in the lead, and see what happens next.

Conclusions: If HII fails to step up and change, it will fail.

If HII fails (or is simply neutered by being uncompetitive), the U.S. Government will be looking down the barrel of a Fred Harris-led shipbuilding monopoly (Mr. Harris is the chief of GD’s Shipbuilding Enterprises, and the effective King of America’s naval shipbuilders. His photo is on the right). I’d be fine with a fleet full of General Dynamics products, but the taxpayers might disagree with the price they’ll be paying, and a large number of suppliers/defense contractors would be concerned as well.

A healthy HII makes sense–it offers an industrial base that the U.S. would be loathe to reconstitute. If HII can preserve itself over the near-to-mid term, the growth of China’s Navy will reinvigorate U.S. naval shipbuilding (and thus brighten HII’s prospects) over the longer-term. But I don’t know if HII will make it. HII has gotten warning after warning, and little has changed.

If status quo wins out, and HII keeps sailing towards the rocks, the Navy and the Government might do well to get tough on HII, and stop helping HII stay healthy. If HII still doesn’t respond, then the Government has little choice to resign itself to letting capitalism “Take Its Course”, and make do with a General Dynamics-led monopoly on naval shipbuilding–at least until another hungry shipyard (a Foss, a Vigor Industries, an Eastern, a Bollinger or even BAE) steps up to fill the large-and-complex-ship industrial base a sclerotic and ponderous HII may vacate.