In continuing the discussion sparked by my recent DefenseOne.com proposal to build a new National Shipyard, let’s take a few minutes to examine maintenance work-load estimates. Even though low-balling the cost of operations and maintenance is an old, long-standing habit in certain parts of the Pentagon, the game is no longer fun, and it needs to stop.

As the DoD budget gets tighter, the Navy must do a far better job of estimating the support it needs to function and then do a better job of relentlessly leading America towards fully funding those needs. That’s easier said than done–it’s tough to get right and no blunt-talking supporter of big O&M spending at a Naval Yard has ever been promoted when a new carrier or sub is at stake. And if the Navy can’t even sell the work of the National Yards to itself, nobody’s gonna be out there selling National Yard O&M work to the public.

The prudent path, given today’s uncertain fiscal, technical and geopolitical environment, would be to raise the profile of operations and maintenance activities and help them seek funding for “excess” maintenance capacity rather than less.

This can be done. For submarines, in the post-Cold War environment, America developed doctrine and funded policy that effectively sustained “excess” sub production capacity for years. The entire enterprise relentlessly studied the challenge of reconstituting submarine production in the post-Cold War drawdown, and ultimately resorted to heroic measures to keep two production yards open that can, today, be ramped up to produce three or more SSNs per year.

But all that gutsy research in the late ’80s and ’90s failed to anticipate the operations and maintenance needs for the 2000’s. Nobody shifted gears and ramped up to meet demand. So now here we are. After demonstrating the Navy CAN do a good job of using data to build support for excess capacity, everybody is discovering that the USN/DoD failed to look beyond the basic procurement process to ensure a commensurate measure of excess in America’s repair/maintenance industrial base.

If we don’t do better, a future Congress will start asking questions like, “Why build ’em if we can’t operate ’em?” And nobody wants that.

Yard Fixes Will Be Slow in Coming:

It is no secret that the National Yards are in trouble and that Navy’s maintenance backlog is creeping up. In recent months, the GAO joined the CBO in an ongoing effort to promote privatization of high-end maintenance for over a third of the U.S. Fleet, and has extensively modeled out the backlog costs in terms of vessel availability. RAND and others have all reported on the terrible material condition of the National Yards.

To address both the backlog and the poor Yard conditions, the Navy has sketched out a leisurely, 21-year, 20-billion dollar plan to recapitalize the National shipyards. While planning out investments over the longer-term is commendable, the data used to support these refits are likely still a bit too “happy” and “lean” to fully trust.

Don’t get me wrong; refreshing America’s obsolete, unworkable yards is a commendable goal. A billion dollars a year in improvements is far better than nothing, and it is great that the Navy has a long-term plan. But…given that we were already planning to spend more than six hundred million dollars in FY 19 on various yard improvements, the actual increase seems low given the articulated improvement goals. And then–as with any ambitious projects on what are, essentially, polluted and highly-utilized historical sites–the going will be far slower and the costs far higher than expected.

So, with those uncertainties in mind, a new yard is in order to help relieve the expected maintenance load. But even aside from the mountain of deferred maintenance, the prospect of “great power” competition alone demands a more aggressive rate of investment and greater dispersion of critical vessel maintenance infrastructures. Add in the potential for a large surge in maritime undersea domain assets, more yard-based support is going to be needed.

But if America needs a new yard, the Navy must move ahead now; shipyards cannot be built and staffed overnight. We desperately need to know if maintenance demand has been estimated correctly, and the record, frankly, suggests that it could be better.

Navy Estimates Are….Unreliable:

Now, those of us who follow the industry know that the Navy has a poor record of estimating (or, worse, acknowledging) the cost penalties good maintenance practices can impose upon upon pressing Navy operations, budgets and procurement goals. We also know that the Navy’s “can do/must do” culture makes it hard for the organization to recognize best maintenance practices “facts of life”. But everybody also needs to understand the challenge the Navy has in integrating future goals for the wider undersea enterprise–some of which may be deliberately obscured from public view or even classified–with maintenance requirements. It is impossible to integrate semi-secret enterprise goals with pedestrian concerns like maintenance. You simply can’t defend externalities you can’t publicly acknowledge. So with all those uncertainties we all need to recognize that the odds are stacked against good estimates.

The first step in building stronger O&M cost estimates, Navy policymakers must get about acknowledging a root cause for the current sub maintenance conundrum–the fact that the assumptions employed to justify deep post-Cold War cuts to naval maintenance resources were wrong in the first place, and that the existing maritime support infrastructure is now woefully undersized because of it.

The background to this hasty drawdown is illuminating for all maritime and national security policymakers. 1993 BRAC participants, in justifying the abrupt 1996 closure of two submarine maintenance centers, California’s Mare Island Naval Shipyard and South Carolina’s naval shipyard in Charleston, were locked into using the short-term time horizon of the FYDP (and a prediction of a far smaller sub fleet) as a basis for their recommendations. But this short-term timeline, in itself, should have been stopped cold by naval stakeholders–in the business of nuclear ship repair, where CVN Refueling and Complex Overhauls can take four years to complete, a five-year time horizon is nothing.

But when the BRAC commission was deliberating, the Navy didn’t help itself. It couldn’t. At the time, it was locked into a procurement vise and couldn’t dare argue for additional maintenance capacity.

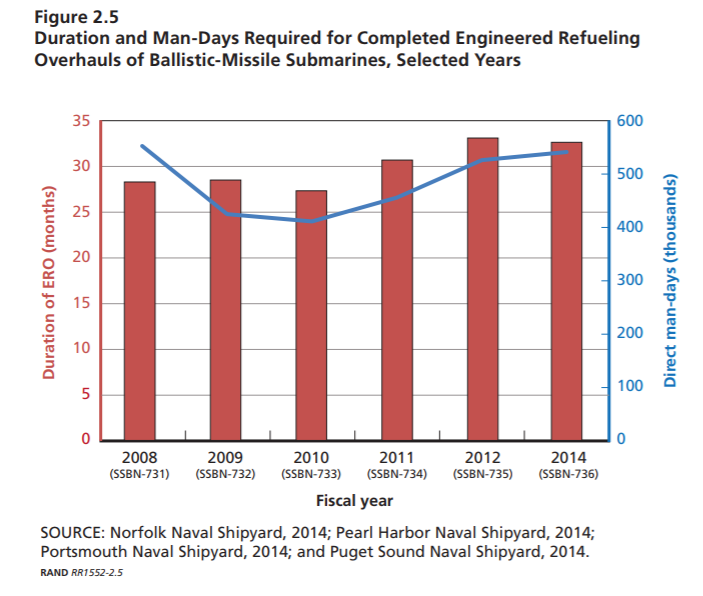

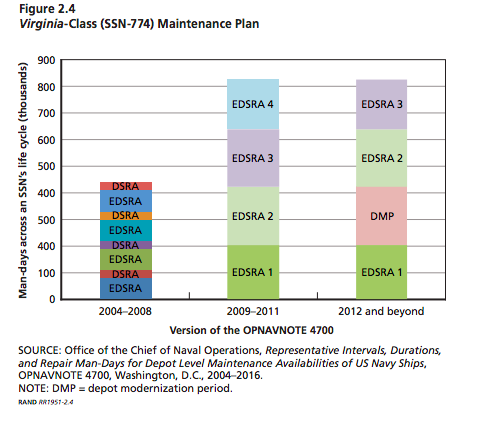

You see, the 1993 BRAC deliberations took place just as the Seawolf program was dying, and Navy was desperately using the promise of lower maintenance and life-cycle costs to sell DoD and Congress on a new, low-cost attack submarine, the platform that eventually became the Virginia Class SSN. And just as the bills for the mid-life refueling of the Los Angeles Class SSNs were starting to come due, Congressional stakeholders were salivating at the prospect of a new sub, with a new, purpose-built reactor designed to last the life of the submarine. As part of the value proposition, a cut of 400,000 to 500,000 days of maintenance work needed for each Engineered Refueling Overhaul (see the graphic above, from RAND), allowed the Navy to convince itself–and the BRAC Commission–that Navy Yard capacity wasn’t really needed. The models said the small sub maintenance yards were expendable.

But, as the sitcom “narrator voice” meme tells us, “They were wrong.” RAND reminds us that, once the Virginia Class SSNs entered service in 2004, it only took a few years for the Navy to quietly double the original estimated lifetime requirement of 1700 work-years of shipyard maintenance (see the chart below). With the rebasing, each Virginia is now expected to need about 3400 work years over the course of each sub’s thirty-year service life. But by then–2009–all that extra Cold War yard capacity that could have absorbed this surge in future demand was long gone, handed over to private entities for pennies on the dollar.

Put another way, the Navy sold the Virginia Class to Congress on the promise of avoiding the added maintenance/cost burden of an Engineered Refueling Overhaul (an ERO). EROs demand a substantial amount of yard labor; refueling early Los Angeles Class boats required between 450,000-462,000 man days to complete and the Ohio Class (see the chart from RAND at the top of this section) needed somewhere around 400,000 to 500,000 of direct man-days. But in an ironic twist, the added 1700 work years of maintenance requirements for the Virginia subs roughly equates to an additional 443,700 man-days of maintenance per sub. Somehow the pre-procurement O&M estimates missed an ERO-worth of O&M work! Per hull!

How does that happen?!

It’s still somewhat mind-boggling that the Navy got away with adding an ERO of extra maintenance to every single one of these supposedly “ERO-less” Virginia Class submarines. Nobody even got fired! But the facts remain…while the Navy got to procure a new sub, it sacrificed the maintenance facilities needed to actually maintain them.

In aggregate, the maintenance hit is really substantial. If these maintenance numbers hold up over time, the presumed full fleet of sixty-six Virginia Class attack submarines are set to gobble up the annual two million man-days currently allotted to by the National Yards for submarine maintenance, leaving nothing–NOTHING–for other stuff. Theres just no time left for decommissioning of existing subs or maintaining existing Seawolf Class attack submarines, the Ohio Class or Columbia Class ballistic missile submarines….or any other cutting-edge undersea platform.

The Virginia Class may be a harbinger of things to come…other new programs have likely underestimated their O&M demands as well. As the Ford CVN and the Columbia Class SSBN come online, all us taxpayers should expect that initial Navy maintenance estimates will fail to hold up in the real world, outside of any pre-procurement model. If we add in ongoing efforts to change or shift the existing programs of record, the Yard situation is going to get really sporty, really quickly.

Think about it…Future Los Angeles Class Service Live Extensions, continuing Virginia Class program modifications (and structural modifications), and possible Columbia Class program of record changes are going to make unprecedented demands upon our maintenance infrastructure. It’ll mean serious problems unless we have some excess capacity ready to roll in a few years.

And we intend to absorb all this while fundamentally upgrading the yards at the same time?

Good luck with that!

Look. Perturbation of O&M estimates can, with savvy leadership, be anticipated. We’ve seen abrupt program-of-record changes happen before. For example, the conversion of SSBNs to SSGNs has long been something of a tradition; for decades, as new SSBNs came online, a few remaining older generation boats were converted into “conventional” missile boats or special, uh, SEAL taxis. But, somehow, as discussions of the downsizing of the Ohio Fleet were underway in 1993-4, a conversion plan failed to be baked into long-term Navy maintenance plans as a contingency. So just as the BRAC closure of sub yards took place, the newly “right-sized” sub maintenance infrastructure got socked with a big conversion and maintenance tasking that it (in hindsight) simply wasn’t prepared to handle.

We have also made things worse by papering over basic systems engineering challenges. The failure to integrate Ford Class carriers and Virginia Class submarines (and likely Columbia Class SSBNs) into existing maintenance facilities is tough to explain. If we are so cost-constrained, why are we building a carrier that juuust can’t fit into the existing dry docks? Or propose an SSN insert that makes SSNs juuuust a tad too long to fit in legacy infrastructure? Was anybody besides industry thinking about this beforehand? If not, why not?

So, with these things in mind, I just can’t accept the assurances that all is well with the Navy’s blueprint for future sub maintenance. We may be moving in the right direction, but the Navy still needs to demonstrate it is capable of accurately estimating maintenance needs. The Navy must do a better job of justifying additional capability to support likely emergent program changes, classified programs, demand shifts or strategic changes. If it cannot, then the Navy needs to bite the bullet, tell Congress that the estimates are uncertain and that the only way to mitigate the uncertainty is to provide the Navy’s National Yard infrastructure with added capacity.

Conclusion:

In short, the Navy needs leaders who are willing to shove aside the “happy estimates” and willing to “damn the torpedoes” in arguing for more Yard capacity. The simple truth is that the Navy needs slack within their maintenance infrastructure–and, to me, that slack is likely best delivered by a new National Shipyard.

We will continue this discussion. Keep the cards and letters coming!

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

I suspect that NIMBY opposition would await several candidate sites, especially on the West Coast. We’re talking sub-intensive work and that means nuclear reactors on the waterfront. I spent four years at the now-closed Mare Island shipyard (SF Bay Area) and now live near the naval sites of Bremerton, Bangor, Everett and Whidbey Island, WA. The active bases and shipyards are somewhat “baked in” to communities, but starting a new shipyard is an entirely different political dynamic. Mare Island was easy to close (though a major hit to Vallejo), but reopening that sub yard is a non-starter similar to reopening the Yucca Mountain, NV nuclear waste repository. Coastal ‘elites’ want “new economy” jobs brought to their cities, not uranium and plutonium jobs. I wish it were different.

The path of least resistance is to expand capacity where this work is already amenable at existing shipyards. The next best approach is a new yard just up the road or down the river within the same communities.

How about Port Hueneme?

My pick would be the “former” BAE yard in Mobile, Alabama.

We could probably pick up a shipyard cheap in Philadelphia..