Let’s talk sub proliferation! It’s no secret that, for any “on-the-move” developing country, an operational indigenous submarine production capability is the “hot” “must-have” naval accessory.

Let’s talk sub proliferation! It’s no secret that, for any “on-the-move” developing country, an operational indigenous submarine production capability is the “hot” “must-have” naval accessory.

And that’s great. Done right, sub production is an audacious industrial achievement–an exercise in manufacturing mastery, where precision, quality and engineering innovation come together to ensure the survival of humans hundreds of meters below surface.

It’s not entirely a win-win proposition, though. Aside from the prestige of joining a small-but-growing club of elite international manufacturers, sub production–if a country can’t export their products or maintain a steady production line–comes with surprisingly few lasting strategic or economic benefits. Unless fed, all that fancy infrastructure just…crumbles.

But developing countries just don’t seem to care. I don’t know what it is, but, with subs, rationality just seems to go out the window. Egged on by an eager array of sub salesmen (from France, Germany, Sweden, South Korea, Russia, Italy….even Spain), far too many countries underestimate the steep price of admission as they rush off down the “standard” developmental pathway–going from buying sophisticated foreign subs to building SSKs from kits/prefab modules and then moving to licensed production and beyond.

First Subs Are Usually Pricey, Decade-long Experiences in Pain:

First Subs Are Usually Pricey, Decade-long Experiences in Pain:

It’s often a case of countries biting off too much complexity, too soon. Frankly, I am unaware of many countries whose initial experience in large-scale, sophisticated submarine manufacture ended happily, with a product delivered on-time, on-budget and trouble-free.

Many countries find their flirtation with submarine production to be too big of an investment to complete, and quit, mid-program. Argentina failed with the TR-1700. Greece’s court-encumbered effort to domestically produce the Papanikolis Class (German Type 214) is a festering sore that is likely not to be repeated soon.

Sustainment is a problem. Several countries produced good subs (and darn good subs at that), but found the investment too hard to sustain. Australia’s experiment with the Collins Class sub may well have driven that country out of the sub production business. Even the Netherlands may step out, and not replace their well-regarded (and home-produced) Walrus Class.

But, difficult as it is, sub production is here to stay, and, despite flailing in their initial efforts, other builders will stay in the game, building/developing subs outside they purvey of the the standard “legacy” sub designers/builders–Sweden, Germany, Russia and the U.S. But moving from kit-built to producing a foreign design and then to domestic production of a local design is not a fun process.

Pain just seems to be part of the agenda.

Rough starts are legion.

Brazil’s experiment with producing German Type 209/1400’s (the Tupi and Tikuna Class) was a mess–It took the first Brazilian-built Sub nine years to go from a keel authentication into naval service.

China–and we won’t belabor China’s evolution here as we are focusing primarily on the proliferation of Western designs–mass-produced shoddy knockoffs of Russian subs for decades, and then endured her share of issues and challenges as the country transitioned to home-grown designs.

India’s effort to kit-build two S-44 Shishumar Class (a German Type 209/1500) was a rough experience (years late and costing twice as much as the German-built subs), and their effort to build a French Scorpene (Project 75) is probably going to see the first hull enter service after an epic ten-year build cycle.

Spain’s experience producing the S-70 Agosta Class with French help was rough, and their subsequent independent effort has led to an overweight S-80 Class.

Pakistan’s first home-built Agosta-90B Class sub took more than ten years to build.

The outcome of Indonesia’s effort have South Korea’s Daewoo Corporation hand over enough knowhow to build a Type 209/1400 has yet to be determined.

(I’ll reserve a discussion of Iran and North Korea’s sub production efforts for later.)

So…out of all the pain and suffering accumulated by our intrepid cadre of aspiring sub-builders, has anybody identified the markers of success? Surely some wizened old coots in Langley (and in a host of similar institutions) have boxes full of half forgotten dissertations with anodyne titles like “Industrial indicators for favorable completion of pressure hull manufacture: A comparative study between states”?

If so, they’re not sharing. But, by now, us lowly open-source-dependent folks have a big enough of a data set to start teasing out some ideas as to why some countries have been more successful their first time producing than not. In my cursory survey, Italy, Turkey and South Korea stand out….(I might have elevated Pakistan to this list, but for their small program and their ugly experience with their first Agosta).

It’s not that these countries were hugely successful in their first attempts either, but Italy, Turkey and South Korea stand out in that their sub-building efforts have been relatively less trouble-free in comparison to all the rest.

What made them different?

Infrastructure: By and large, they all had a strong foundation in naval or commercial ship-building infrastructure.

Funding: All amply funded their programs, orienting themselves towards supplying either large operational sub fleets or the export market…or both.

Type: All started with a German design and German technical support (!)

Two of the countries had the benefit from being in, essentially, the same military/industrial bloc as their primary supplier, allowing for a relatively smooth and orderly progression as native suppliers replaced foreign-sourced kit.

I also suspect that all the countries had a good understanding of their national engineering and manufacturing capabilities, and they consciously didn’t over-reach or demand a higher percentage of locally-sourced sub-ready materials than their economies could readily supply.

But that’s not all.

Building ‘Em Trumps Reverse Engineering:

Building ‘Em Trumps Reverse Engineering:

What is really interesting about the countries with more “successful” sub-building programs is that several of those countries had tinkered with mini-sub production. (Now, I’ll caveat this by saying that national minisub development/manufacture aren’t covered deeply by the usual open-source outlets (hint, hint guys) so take this observation with a big grain of salt, OK?).

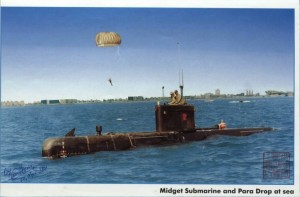

Caveats aside, contributions from mini-sub production is something that, I suspect, is underestimated as a risk-reduction exercise. Mini-sub programs are easy to overlook and a little harder for host countries to justify–they’re not shining and dramatic examples of national manufacturing prowess, and, unless produced in numbers, they don’t turn the needle strategically. They’re often dismissed as curiosities–or low-status gear that only an impoverished, desperate country like North Korea or Iran would use (which, uh, they, um have actually used to, ah, sink stuff).

But that’s the point.

Mini-subs–successful or not–give the builder a taste for the complexities of sub manufacture, and allow the building country a low-pressure/low cost way to develop a small cadre of competent manufacturers, designers, operators, maintainers and suppliers before jumping into a “large-scale” SSK production program. A mini-sub failure is a lot less of a big deal than, say, screwing up your shaft alignment in your first full-scale SSK.

I’ll even wager that “learning-by-doing” with mini-subs offers more longer-term advantages to the host country than, say, a wholesale effort to reverse-engineer larger-scale projects or intel takings. China may have produced a ton of low-tech Russian knock-off subs, but all that production-by-reverse-engineering didn’t keep China from suffering in their transition to (cough) largely home-designed (cough cough) submarine production.

There’s a world of difference in having a blueprint to follow and understanding, through first-hand experience, just why the sub you want to build is built the way that they are.

If pressed, I’d even suggest that mini-subs do more for the host-country’s basic sub-building infrastructure than, say, refits of existing submarines. Certainly, conducting successful refits of existing platforms should be interpreted as a potential indicator of future sub-building (I’ve written about that here), but…in itself, successful refits don’t guarantee that an initial attempt at sub building will be pain-free. Lots of countries in the list of “pain” above had been successfully maintaining their boats for years and refitting ’em.

Submarines will continue to proliferate, and countries will continue to try and build their own boats. But it’ll be interesting to see if other countries learn from their predecessors–or if they continue to make the same mistakes everybody else has made–and end up spending, on average, a decade or more building their first home-brewed boat.

But by now, there’s plenty of data to allow aspiring sub-builders to make more informed decisions. Given the importance–and greater appreciation of–unmanned or smaller subs, I’d expect quite a few other countries are out there right now, tinkering with their own “small boat” design (How is Chile’s domestic-built Crocodile Class mini-sub-building effort doing anyway?).

If mini-subs do actually serve as a positive indicator for successful initial prosecution of full-scale sub production, I’ll also be quite interested to see how the nexus of South American sub-oriented smuggling hybridize and inform future sub-building efforts in South America. Plenty of U.S. naval innovations came from smugglers, and, well, at some point, somebody’s gotta break that lock Sweden, Germany and France have on the export sub market!

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

No mention of Japan?

Also worth mentioning the extent to which even Spain which ticks a lot of your boxes, has needed quite a lot of help from BAE in Barrow for the complicated bits of the S-80, and has used a number of other suppliers to the British SSN programme.

The other issue is sustainment, these things need looking after to remain effective. Argentina in 1982 is one example, also the way in which the Upholders really suffered during a relatively short period of mothballing before the Canadians bought them.

Yeah, I know, sorry. Couldn’t speak to Japan’s sub work. Love ’em though, and can’t wait to see them hit the market.

Interesting point about Spain. I’m interested in how Australia turned it’s back on their long-term relationship with the UK (and all the sustainment support and so forth) with the Collins Class procurement.