There is a long-standing idea out in the world of “amphibious assault” that connectors (those things that are supposed to move from a ship to a beach and back) should be pure logistical creatures.

With Operational Maneuver From The Sea, the idea of fighting in the space between the ship and shore is almost a complete non-starter.

I urge that we all reconsider…and start thinking about how connectors, their cargo–and even those odd “Amphibious Combat Vehicles of the future” might fight at sea.

A good place to start reconsidering things is Oscar E. Gilbert’s vastly under-appreciated book, Marine Tank Battles In The Pacific. It is a must-read for anybody interested in how the Navy’s infantry struggled to understand and use armor–and connectors–to fight not just on shore, but in the space between ship and shore.

The book is, quite simply, an exhaustive (and entertaining) catalogue of major (and some minor) tank actions in the Pacific during World War II. (A perfect gift for those who might be considering a Pacific Pivot in their future!)

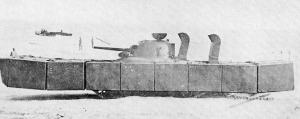

The book is chock-full of little-told niche stories–like this one, the story of the T6 Floatation Device–a contraption allowed a Sherman tank to swim ashore and fire the main gun while afloat (envision the Monitor ironclad with a Sherman tank turret–47 Feet long!). A great discussion of this floatation device is available here.

It also set the stage for the first (and only?) tank-rams-destroyer moment. Gilbert writes:

It also set the stage for the first (and only?) tank-rams-destroyer moment. Gilbert writes:

The T-6 consisted of six large steel floats attached to the tank, which turned it into a low, turreted raft. Special brackets welded to the front and rear held detachable pontoons, and smaller non-detachable pontoons were welded to the sponsons of the tank.

Bill Henahan was a driver on one of the tanks fitted to the T-6: “Down below where we used to fasten our towing cables and such, they had brackets. They had pins that went in down there, and the pins were wired to a switch in the driver’s compartment. These pins had an explosive charge on the end, and they would shoot out and the pontoons would fall off. You had to warn people away, because the pins would fly a couple of hundred feet, and they were pretty good size. They were a couple of inches in diameter and six or seven inches long. The side pontoons provided no extra protection, but they were welded directly to the hull. They stuck out close to sixteen, eighteen inches. You couldn’t get in and work on the suspension system.”

Propulsion was provided by churning tracks, which were equipped with special track connectors that incorporated cup-like cleats like those on the tracks of the LVTs. Top speed in the water was only about half that of the armored amphibians, about two miles per hour. The tank commander stood on the deck behind the turret and pulled two ropes to control crude rudders.

One major problem with the T6 was its size, which imposed a serious penalty on transport space. The device was also awkward to jettison. The driver had to blow off the two rear floats, pull forward several yards, blow off the front floats, then back out from among them. The most serious tactical drawback was the front of the hull. If the hull front grounded on a submerged obstacle the tracks were still floating free, preventing the tank from simply scrambling over like an LVT….

….[at Okinawa] A handful of tanks with the T6 Floatation Device were dropped an hour late and 10 miles offshore. As a test of their seaworthiness it was a success. As a tactical measure it was absurd, since it took the tanks five long hours to work their way to the reef edge.

The lead tank of the 1st Tank Battalion detachment, commanded by Sergeant D.I. Bahde, immediately ran afoul of a passing destroyer. Unable to speed up, slow down, or steer adequately, the tank plowed inexorably toward the ship, which refused to give way. The tank crashed into the side of the ship, achieving the dubious honor of being the only tank ever to ram a ship at sea.

So what?

What can a modern-day Marine learn from this story?

Well, OK, yes, I know that the first lesson is to not take on a Destroyer with your fighting connector. Got it.

(For those of you wondering, the hapless tank from this story stayed afloat long enough to strand itself on a reef, and then sank. But the crew got out with a bottle of bourbon and a large can of peanuts–that I think the Destroyer crew handed down to ’em. (The Marine Corps Tankers Association apparently has the full story).)

But what else? Well, consider endurance. The tanks, when they reached the reef, were unable to climb the underwater break, and ended up chugging miles away to the 6th Division beaches….So they ran up to 10-12 miles at sea–enduring five to six hours of constant operation–before entering battle. All without running out of fuel. Imagine how they might have been more useful if given better doctrine (and comms) to provide close-in fire support from the surf. I mean, is anyone besides the Swedes and Finns thinking about this?

Our second selection from Marine Tank Battles of the Pacific offers a little tidbit from the Marine Corps’ 1943 campaign to take New Britain–detailing one of the first attempts to use embarked tanks to fight at sea:

Our second selection from Marine Tank Battles of the Pacific offers a little tidbit from the Marine Corps’ 1943 campaign to take New Britain–detailing one of the first attempts to use embarked tanks to fight at sea:

The Japanese began to evacuate the small harbor at Talasea on the opposite side of the Peninsula, but on their second run the boats were all sunk in a running gun battle with American torpedo boats. For several nights American landing craft fought night actions against the enemy landing barges.

To plug this escape route, a small force supported by a section of C Company’s light tanks was carried around the peninsula to attack Talasea on 9 March. Rowland Hall related: “We re-embarked them [three light tanks]. As we went around the tip of the peninsula inshore we spotted some Jap landing craft. We opened up on them with the 37 and machine guns. We bagged about three of those and set them on fire. A sort of naval battle using tanks.

The New Britain campaign also saw Marines placing M4A1 Sherman tanks on Army LCMs to compensate for the absence of Naval gunfire support, too. Didn’t need to use it though, since there was no opposition at the landing…

The New Britain campaign also saw Marines placing M4A1 Sherman tanks on Army LCMs to compensate for the absence of Naval gunfire support, too. Didn’t need to use it though, since there was no opposition at the landing…

I love the concept. The tank-landing craft combination has been used on-and-off for years now–at D-Day, in Vietnam, Grenada…but it’s always come across as an ad-hoc effort. It’d be nice to be able to revisit this idea and formally study the use of embarked amphibious tanks (or connectors) as a way to quickly “bulk up” the hitting power of their attendant amphib.

Imagine how hard it would be for a swarm to suddenly be faced with 10-15 small, fast-moving and relatively well-armored gunships? That all carried rapid-firing 30mm guns? Why…that’d be a daunting command-and-control challenge even for the most accomplished Boghammar commander…

Active discussion of how the contents of the average amphib’s well deck could be applied to better support the fleet would be darned interesting. I mean, if I were in a Boston Whaler, and I ran into an LCU carrying a ready-to fire Abrams Tank (or, say, a free-swimming, mortar-wielding amphibious tank), I’d run in the other direction as fast as my outboard motors would let me.

This sort of unpopular niche capability might be an interesting avenue for the Army to build USMC/Navy collaboration–but–please–only after Army helos are fully integrated into this “thing” we currently call Air/Sea Battle! (Which reminds me…when is the Army going to get around to trying to reactivate their old (and once-numerous and “connector” filled) Navy, anyway?)

See you on the beach! Great discussions ya’ll. Really appreciate it.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Each attempt at snap-on/ejectable flotation has been a dud, and snap-on propulsion I don’t think has ever been tried. If this is researched again it would likely not work for tanks, but maybe personnel carriers. Financially, a key sweet-spot is flotation that may be disposable in wartime (drop and forget), but reusable in peacetime much like fuel drop tanks on tactical jet aircraft.

The frequently conceived side mounted pontoon flotation is slow. It adds drag. But what about putting flotation in front and back instead? The LCU-F concept, which doubles the speed of an LCU by folding into place an elongated stiff hull form, turns a naval ‘brick’ into a cigar boat shape that can more swiftly negotiate most any sea state without over-crowding an amphib well deck. I’d be curious if this has been researched for armored vehicles. The cancelled EFV lengthened itself by thrusting a planing surface forward off its front hull, but that may have been an attempt to limit a pitch forward effect from the speedy propulsion. It also had to be retracted in the surf zone before touchdown on the beach.

So my first beta test would envision an inflatable sharp bow and inflatable bulbous stern on an already seaworthy (well, lagoon worthy) personnel carrier like a LAV or MPC. Flotation would be hull-forming front and back for a cigar boat shape. Constant air pressure could negate most light damage including small arms fire, and for safety the base hull must float by itself in the event of major damage to the snap-on flotation. Increased propulsion could be achieved with gear reduction on the aft props which are located along the hull sides. (Normally, faster RPMs sink the nose, spills water into the drivers hatch and eventually stalls the speed; this has been limiting speeds on AAVs as well.) Or, shoot, just test this all with hydro software or scale models.

If successful at boosting water speeds by 50% or more, then developing a next generation AAV (ACV) with snap-on for/aft flotation and with speeds reaching 18 mph could be worth pursuing. It would keep AAVs self-deployable, launchable from just over the horizon and not occupying critical landing craft.

I like this idea.

Sadly the EFV, had it performed as advertised, would have been absolutely perfect for swarm defense. Armored, fast, and armed with a fully stabilized cannon it would have given Iranian commanders fits.

It also would have lent itself well to brown-water or riverine ops. Fast moving armored vehicles carrying Marines on raids up rivers or waterways would really be useful.

Back to the post-EFV reality.

If the ACV is a EFV without all the retractable features perhaps they can still make it better in the water. Add a module on the back that has an additional powerplant and is neutrally buoyant. It may not skim the seas at over 30 knots but it will be much better than the current AAV. Then on land it drops the pack for land combat.

The old LCM-8 would be good for carrying a LAV-25 or something similar; I’m sure we have some in storage.

The big problem with placing tanks or armored vehicles on landing craft is the vulnerability of the vessel. It’s great as an ad hoc concept, but it might be an issue for a protracted conflict.

By the way I’d love to see what size a T-6 style float would need to be for a M1A1!

Integrating large bore, direct fire weapons into the surface assault would be an interesting exercise. I do not know enough about the system itself to comment on efficacy, but if you are genuinely under threat and within your ROE you would use every means at your disposal. I suspect cannister would be relatively effective against a swarm of small fast boats.

However, deliberately employing tanks in this manner seems unrealistic if you have the rotary wing assets to deal with them at arms length. I am a big fan of employing attack and armed reconnaisance helos in this role – if you can integrate them into your network. There has been doctrine on helicopter assault group operations for some time now. We just don’t use it.

I invision a catamaran arrangement with the vehicle slung underneith so that just the turret shows above deck level. When the boat hits the beach the vehicle is unslung and can move forward. The catamaran can be any size, but sized to also carry infantry and material in both sides would be ideal.

Please feel free to contact me on a consulting basis.

For a modest fee.