Australia has happily discovered that, for high-end subs, this is a buyer’s market. In Australia’s Collins Class Replacement Project (SEA 1000), eager German, French and Japanese sub venders are offering some top-tier submarine models for some pretty good terms. With all three platforms technically “solid”, I won’t go into technical differences here (look anywhere else on the Internet for that discussion!), but there are a few interesting background issues out there that are quite capable of influencing Australia’s decision. So, without further ado, let’s discuss a few ancillary aspects of the Collins Class Replacement/SEA 1000!

Australia has happily discovered that, for high-end subs, this is a buyer’s market. In Australia’s Collins Class Replacement Project (SEA 1000), eager German, French and Japanese sub venders are offering some top-tier submarine models for some pretty good terms. With all three platforms technically “solid”, I won’t go into technical differences here (look anywhere else on the Internet for that discussion!), but there are a few interesting background issues out there that are quite capable of influencing Australia’s decision. So, without further ado, let’s discuss a few ancillary aspects of the Collins Class Replacement/SEA 1000!

For SEA 1000 to succeed, production must go well.

It must.

Now, I’ve watched Australian naval shipbuilding for some time, and the biggest naval program-killers in all of Australia are production and early service snafus. And as we all know, the process of transferring sub production tech to a non-sub-producing nation is never problem-free. Now, normally, in naval shipbuilding, early production and operational hiccups are not a big deal, but Australia–as far as shipbuilding goes–is not normal.

Australia is a brutal environment for Naval shipbuilders. The Australian electorate has a habit of letting minor teething problems “sink” entire ship classes. Australia’s vigorous, tabloid-oriented press relishes a good scandal and isn’t afraid to delve into defense issues. So with a tiny amount of negative spin (an angry worker, a disgruntled sailor, or a miffed politico), small program problems can easily cascade into a chronic political nightmare. SEA 1000 could become ideal ground for a minority government to hunt down a Defense Secretary (or maybe even a wounded Prime Minister).

The Collins Class itself is a perfect example–the endless string of publicized Collins Class production issues imbued the whole program with a persistent stink of failure. And now, no matter how many interesting and vital–heck, heroic–missions those boats undertake, Collins stakeholders are unable to shake that sense of program-wide malaise. After their long and rocky production process, to the mainstream observer, the Collins Class was a programmatic failure and will always remain one.

Even more interestingly, the damage didn’t stop at Australia’s shores, either…the constant drip of scandal even ate into the Swedish/Australian diplomatic relationship.

So, with that in mind, a trouble-free production process is likely to matter to the Australian political set a good bit (of course, then it appoints a real gem like Donald Winter to the Future Sub Advisory Board, so, maybe Australia doesn’t really care about production problems or bad cost-plus contracts, but hell, what do I know? I’m just a darn blogger!).

But if avoiding production pitfalls–and the subsequent political fallout–really are a major concern for Australian decision-makers, then Australian politicians should seriously consider the Israeli example of buying high-end submarines “off the shelf” and then fitting them out “at home.” There’s a lot to be said for keeping pesky teething and training problems offshore and out of the watchful eye of Australia’s political tabloids.

Sure, “keep-naval-production-at-home” is always a good nationalist bromide, but the apparently seamless transition of the “off the shelf” Spanish-built HMAS Canberra to active duty must have certainly strengthened the case of Australian military/political folks who support outsourcing. It’s all a political gamble–the short-term outrage that vanishes in the face of a strong-performing platform may outweigh the constant political drain of a troubled and pricey technology transfer.

But by now it may all be moot–the outsourcing route may simply not be possible. And that’s fine. If Australia’s political folks have the guts (and smarts) to prep their constituents (and the media) to stand the heat of a rocky technology transfer process, then Australia may see a more successful program.

It’s never too soon to start managing expectations.

But back to production. As I have written before, sub manufacturing doesn’t export very well, but if sub production “at home” is a non-negotiable Australian requirement, some of the more successful sub export/sub production deals (South Korea, Italy and Turkey) have come out of Germany. With France’s record more than a little rocky, and Japan an unknown, Germany should highlight this strength, orienting their offer around a sweet production deal.

Japan–with their very (VERY) quiet subs–may still be the front-runner, but Japan–as some recent Australian handwringing over production issues suggests–doesn’t have a lock on this sale.

In my mind, Japan’s production-related concerns should be dismissed–Japan may not have a record of exporting sub and military technology, but the country has a very long (and quite successful) record of selling and transferring manufacturing know-how. Now, it doesn’t help that Japan’ sub-making yard is something of the maritime equivalent of Willy Wonka’s secretive candy-making works, but I’m pretty sure all the production-related hand-wringing is overblown. If Japan says they’ll transfer tech, they’ll do it. But it may not be an easy meld.

Outside of outstanding tech (I love Japanese deep-diving hull manufacturing tech, I really do), the strength of the Japan offering is rooted in the alliance-base. A sub deal could be the start of a tripartite China-balancing coalition of the US, Japan and Australia–maybe even the blossoming of a “special relationship”. That’s an enormous strength, and it gives Australia natural access to a wide array of US resources–and probably first-dibs on whatever nifty tech that comes out of Japan.

With the producer a short cruise to the north, maintenance and sustainment becomes less of a concern, and friendly ports will suddenly open up throughout the sub’s likely Western Pacific operational area.

But, despite the fact that Japan has one of the best products out there…it might be worth considering what might happen if things didn’t go well–what diplomatic damage could an Australian/Japanese spat over a rough sub production run actually inflict upon the Pacific? And would Australia’s devil-may-care and far-too-lax attitude towards security mean for Japan’s secretive sub-making community? I’d sure hate to see China driving around in subs built with Japanese methods that were pilfered from some drunken Australian engineer who didn’t want to bother with his meddlesome cybersecurity protocols.

But hand-wringing aside, if Japan really wants to make this sale, it might do well to start crafting a blizzard of mutually-beneficial port development/expansion projects in the South Pacific, Indian Ocean and beyond–and getting Australia engaged in this work, ASAP.

Because we can’t discount France!

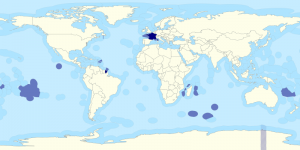

As I’ve said since I started blogging back in, oh, ’07 or so, France has many interests in the Pacific, Indian Ocean and Antarctic approaches–a sprawling set of colonial holdings right in the middle of Australia’s articulated area of interest (see the map above for France’s global EEZ).

It’s all an interesting combination. In the face of an expansionist, “Manifest Destiny” China, France needs friends to help keep their islands and old colonial holdings secure. Australia (which has been actively focusing on the islands of their “near abroad”) might enjoy access to a wider array of regional bases and ports in their area of deep strategic interests.

Now, the French, if they are serious about making a sub deal (and they are, believe me), should be making a serious effort to move beyond eloquent White Papers and get busy forging bilateral agreements with Australia to work in tandem in mutual areas of interest. The upcoming dispatch of a huge French trade expedition is, I presume, part of that effort.

Another thing to think about is that a purchase of French subs also keeps Australia’s options open–lashing up with France is still a China-balancing play, but a tad less provocative than going and buying military gear directly from Japan. And while America (and Japan) will likely be cranky if Australia goes with a European option, Australia is too important for America or Japan to do much more than grumble. The Australian alliance is gong to happen regardless.

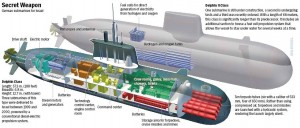

In Japan and Germany, we have two coastal submarine specialists competing with France, a country struggling to secure a sprawling set of world-wide assets. So it’s worth wondering if France is intuitively more focused on design features that have more in common with Australia’s current operational practices (But then again, when these boats start entering service, contested seas of interest to Australia may be a whole lot closer than they once were).

In the Pacific, I like the idea of a big hull-form, good margins and lots of room for ammo and…things. That said, all the offerers either have those features or have “grown” their offerings accordingly. France’s design is derived from a nuclear sub, and I speculate that France’s original requirements may prove a more intuitive fit with Australian requirements than the other more coastal-defense oriented subs provide.

I also like the idea of taking a nuclear hull-form and deriving a conventionally-powered design from it. That all may be something of a DCNS/Thales marketing gimmick (it’s gotta be a pretty big redesign), but it’s also a route Australia might use to build it’s comfort-level to, ultimately, cajole voters into considering the use of nuclear power in a next generation submarine (which France would be thrilled to supply, of course). My only concern here is that France’s technical solution for the conventional sub might be a tad risky.

Finally, there is an argument to be made for simplicity. If Australia is going to build this sub at home, the Government needs to be focused on keeping that undersea industrial base healthy over the long-term. And that means keeping the industrial base active, building deep water things–unmanned undersea vehicles, mini-subs and so forth.

So, I…guess I hope Australia considers sticking to the basics A nation just can’t build a viable industrial base if it starts with a gold-plated craft–it just can’t. But if Australia starts simple with a good-sized, high-margin boat that can’t really fail–some torpedoes in a can, with a few advanced features that don’t break the bank–the country will have a chance to get some “wins”, popularize their submarine cadre, build a sustainable training/crewing and industrial foundation, and use that foundation to make and field advanced undersea craft, pushing into a new area of technology.

And that’s the future. That’s where Australia has a real opportunity. But countries don’t get there by deploying regional “unobtanium” they can’t maintain, operate or sustain.

Conclusion:

Pick any of the subs on offer–but just get production right.

If Australia gets a deal that guarantees production hiccups will either not happen, not get noticed—or be promptly solved when they do, then that deal (particularly if it guarantees licensed production) is the right one to pick.

Either that, or Australia needs to do far more to prepare their public to understand the challenges going forward with an ambitious, highly technical project like SEA 1000.

All Australia needs is a good, seaworthy boat that the crews like and are able to operate. If that happens, then the program will take care of itself, developing into a sustainable project over the long-term. Something that’s too technical, too balky or too fragile will be a “disaster”, just like the Collins Class was.

So, in closing, Australia, don’t build another Collins. Build something better! Good luck!

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

if Australia goes nuclear power on submarines, they should build Astute class.