The U.S. Navy’s desire for a direct Navy-to-Navy Hotline with China is not new, and has been articulated every few years to little or no effect.

The U.S. Navy’s desire for a direct Navy-to-Navy Hotline with China is not new, and has been articulated every few years to little or no effect.

If direct Navy-to-Navy Hotlines between operational commanders have the potential to be important in Asian crisis management, then the U.S. Navy must start leading an effort to 1) make bilateral Hotlines more ubiquitous in the region than they are today and 2) demonstrate their utility by publicly using the existing Hotlines more often.

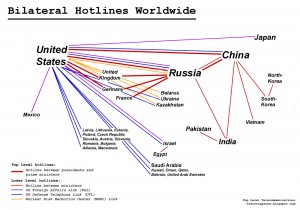

In Asia, Hotline “use” and Hotline “ubiquity” are two things that are not often discussed, but if they were talked up a bit more in the U.S., I think the general public here would be surprised to see that, while Europe and the Middle East are replete with bilateral Hotlines to the U.S., Asia has (as is usual for the Europe and Mid-East-focused diplomatic set) lagged behind.

It is interesting to note that China has apparently established more “official” Hotlines in the region than we have (Who knew China has open lines to Russia, India, Vietnam and South Korea?!). Of course, for the U.S., existing personal contacts or command structures may obviate the need for American bilateral Hotlines in certain places in Asia–But, if the goal is to establish a Hotline with China and get ’em talking, it might be wise to generate a few more U.S.-Asia Hotlines than we currently maintain and start publicly using them.

The other item to note here is that if China seems to value Hotlines enough to have established a handful with other less daunting rivals, how is China putting those bilateral Hotlines to use?

If the “official” Chinese-US Hotline is any guide, Hotlines with China aren’t used for much. The Beijing-Washington line went up in 2008 (after a rough 2007), but the hotline went unused during the next crisis–China’s early 2009 confrontation of the USNS Impeccable. As news reports said:

Gates confirmed he did not use a newly established military hotline between the United States and China over the naval standoff, and said he hoped the incident in the South China Sea would not damage military ties with Beijing.

Gates may be obscuring a point–somebody else might have used the line–apparently, at some point between the 2008 establishment of the Hotline and the USNS Impeccable incident, both Admiral Keating and CNO Admiral Roughead availed themselves of the Washington-Beijing Hotline and found it wanting:

Gates may be obscuring a point–somebody else might have used the line–apparently, at some point between the 2008 establishment of the Hotline and the USNS Impeccable incident, both Admiral Keating and CNO Admiral Roughead availed themselves of the Washington-Beijing Hotline and found it wanting:

China hasn’t responded to PACOM’s proposal for a direct link between Keating and his Chinese counterpart, Keating said. He noted, however, that Navy Adm. Gary Roughead, chief of naval operations, recently used the Washington-Beijing hotline, and that he has used it as well from his Hawaii headquarters.

“But it is not a direct link from me to my counterpart,” he said.

So, between 2008 and mid 2011, the Hotline was only used four times–we can assume once by Roughead, once by Keating, and once for ceremonial purposes:

So, between 2008 and mid 2011, the Hotline was only used four times–we can assume once by Roughead, once by Keating, and once for ceremonial purposes:

One of the four calls was from Defense Secretary Robert Gates to congratulate his newly promoted Chinese counterpart in April 2008.

“We have yet to test it in a crisis,” said Bonnie Glaser, a senior fellow in the China program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington and an adviser to the U.S. government on East Asia. “It remains to be seen which senior Chinese leader would be ready to use it.”

It’s been used four more times between 2011 and mid-2013. And, apparently, at least according to the South China Morning Post, China has cut the line twice to express displeasure over some perceived snub or insult.

Now, when current PACOM Chief Admiral Samuel Locklear called for a direct hotline to his direct counterpart earlier this month, the language was interesting–and regional.

Now, when current PACOM Chief Admiral Samuel Locklear called for a direct hotline to his direct counterpart earlier this month, the language was interesting–and regional.

“I would say that we — that both in the region and in our mil-to-mil relationship, that we need to move forward to — to allow that type of direct dialogue in crisis situations. We’ve said this on many occasions.

I know that Chairman Dempsey, Secretary Hagel, and at that level that there are an occasional attempt and opportunities to have dialogue at that [editor: assumed senior] level. And would that work at the time of a crisis? We would hope it would work.

But internal to the PACOM AOR, I don’t have the ability to pick up the phone and talk directly to a PLA or PLA navy admiral or general at the time of a crisis. And we need to work on that. So we’ve talked about it, but things take time.

It is intuitively obvious for Americans raised in the Western Cold War context that a direct Navy-to-Navy communications link between operational commanders may be helpful in working through certain issues, while we don’t realize that, in the East, mid-level officials may consider direct contact with their rival peer to be something of an anathema. (But then again, if the China-US has only been used eight times in seven years, then we’re sure not making many calls and working to “de-stigmatize” Hotline use or improve the Hotline’s value to China either.)

That’s why it might be quite interesting to see how China uses their other Hotlines, and, if they are as under-utilized as the existing US-China Hotline, to publicize that fact.

It might also be interesting if we did a better job of popularizing Hotlines throughout Asia. If we assume Hotlines make good diplomatic tools, then it makes sense to help build demand for “official” Hotlines. Would it not be wise to make them ubiquitous in the region? Would it be a problem to encourage more small and friendly regional Navies to establish a direct Hotline to Admiral Locklear or other naval leaders then…to use them? Publicize them? It can’t be bad to make these things part of the regional mil-to-mil communications toolbox.

It’s a strategy we may be trying, as, over the past few months, Australia and Indonesia along with Taipei and Manilla agreed to establish bilateral Hotlines. And, conveniently, Japan and the U.S. just announced direct person-to-person Hotlines in January, just as Admiral Locklear was voicing his concerns.

Japanese and U.S. military officials and related ministers have previously used secure telephone lines to speak with each other, but this will be the first time that a private telephone line is established between the offices of individual officials. The U.S. will send engineers to Japan soon to work out encryption and other technical details of the planned hotline.

The Cold War taught us that Hotlines were useful tools. But, like many things in the Cold War, those useful diplomatic tools never quite made it to Asia.

The Cold War taught us that Hotlines were useful tools. But, like many things in the Cold War, those useful diplomatic tools never quite made it to Asia.

That should change.

In Asia, we can no longer afford to rely on productive un-official contacts to get things done in a crisis. Yes, we can continue to use the unofficial “Grenada Template” (Remember when an officer engaged in a firefight on Grenada found that a phone call to friend in the Pentagon could relay fire calls faster than his “official” comms?), or hope that regional professionals will develop their own, private channels (and are brave enough to use them in a crisis–like the doctors who jumpstarted the global disease-response process after sneaking SARS-infected blood out of a mute, non-responsive China). But, as tensions continue to rise, that’s a dangerous route. In tense times, officially-sanctioned bilateral communications are a good thing.

And if China doesn’t want to play, so be it. If the Navy leads the charge (dragging the slow-moving State Department along with it) in establishing Hotlines with friendly Asian countries, China will follow—and maybe, just maybe, the stigma of talking to rival peers will wear off.