This might be an unpopular thing to say, but crooks have helped the Navy win wars.

This might be an unpopular thing to say, but crooks have helped the Navy win wars.

That’s right. Take, for example, smugglers. The pressure of smuggling–the need to constantly innovate to avoid confrontation–has, over the years, done wonders in pushing new technology into the fleet. And the Navy should take some time to acknowledge the contribution and get to understand the tech-transfer dynamic a little better.

Consider, first, the Civil War Blockade of the South, where blockade runners moved naval shipbuilding ahead by turning to steel as a lightweight alternative to iron. From a Naval History and Heritage Command “Daybook” on Civil War Technology (.pdf):

Steel was perfect for Civil War blockade runners. These ships were designed for speed, not combat. They were a wonder of technology, as they were among the fastest ships afloat. British maritime architects designed sleek ships that were equipped with powerful engines. A blockade runner’s length to beam ratio was often 10 feet to 1 foot or more. By comparison, a typical U.S. Navy steam sloop had a 6 feet to 1 foot ratio and a “90-day gunboat” had a length to width ratio of about 7.5 feet to 1. The result for a blockade runner captain was a speedy ride.

Within two decades, ironclads were obsolete, and armored steel-hulled ships were becoming the mainstay of naval fleets throughout the globe.

Another example comes from the Rum-Runner era, where smugglers took the lead in adapting aviation engines for maritime use. Here’s Donald L. Caney, writing in an article hosted in the Coast Guard’s nice little online archive, called “Rum War: The US Coast Guard and Prohibition” (.pdf):

The speed of the contact boats had always been important, and now it became even more so. Purpose-built motorboats were now essential and were being turned out in considerable numbers. Only the basics were necessary for relatively short hauls at high speed: virtually bare hulls, thirty to forty feet in length, with as much engine shoehorned in as compatible with a decent cargo.

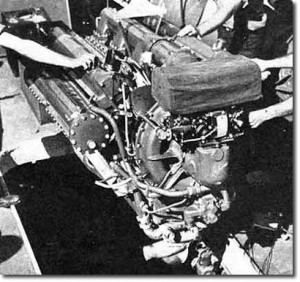

Surplus wartime water-cooled aircraft engines turning out 200 to 300 horsepower were easily found and adapted…Generally, the boats were cheap and astonishingly fast–the rummies would tell you 40 knots…

That innovation enabled development of the World War II-era PT Boat. According to Captain Robert J. Bulkley, in At Close Quarters: PT Boats in the United States Navy, his wonderful summary of PT Boat operations in World War II, gives a little history lesson:

During the 1920’s many other Thornycrofts appeared in sheltered coves and inlets along the east coast, brought to the United States under private sponsorship. These boats were employed in night operations designed to relieve the dryness of a thirsty nation. While the Navy remained relatively uninterested in the development of fast motorboats, the rum trade carried on extensive experimentation, including the adaptation of the Liberty engine to marine use. One engineer whose experience and know-how were valuable to the World War II PT Program was frequently known to preface his comments on perplexing technical problems with the remark “Well, when I was a rummie, we…”

It would be interesting to know how many PT technicians had such a phrase pass through their minds but failed to utter it.

Now, if you believe drug smugglers are just “quick adopters” or are simply making incremental improvements in existing technology, think again. And recall Andrew Jackson Higgins of New Orleans, the “Higgins Boat” (LCVP) designer and rum-runner savior:

Now, if you believe drug smugglers are just “quick adopters” or are simply making incremental improvements in existing technology, think again. And recall Andrew Jackson Higgins of New Orleans, the “Higgins Boat” (LCVP) designer and rum-runner savior:

“In 1924 Higgins had designed a powerful shallow-draft thirty-six-foot boat with a novel underwater hull, for use by rum-runners in the Mississippi Delta during Prohibition. The design was ideal for beach landings because it protected the propeller from striking the bottom and facilitated retraction from the beach.”

This example of how Rum-Runners completely “changed-the-game” comes from First To Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps, by General Victor Krulak.

Obviously, technological exchange is a two-way street, and I am only focusing this blog entry on the cases where smugglers have informed naval technology rather than the reverse–where there are, admittedly, a lot more cases. (Quick, representative example: Look at the drug-runners’ recruitment of ex-Soviet submarine experts to support their efforts to develop subsurface technology.) But I think the creative forge in which smugglers operate is worth examining and understanding. If small, well-funded teams, quick prototyping, incremental improvement, steady pressure to constantly refine operating doctrines, etc. prove successful in developing new tech, then, maybe…it might be wise to replicate that environment “in-house”.

In closing, it is obvious cross-fertilization between smugglers and the military is not a new phenomenon. But with opportunities for community cross-fertilization getting stronger and stronger in areas like, say, cyber, it might be well worth characterizing the exchange of innovation and technology between the two communities so that the Navy might be better prepared to understand and exploit the seam between crooks and sailors.