Mine Warfare in the South China Sea is inevitable.

Mine Warfare in the South China Sea is inevitable.

Look at the players. On one side, we have China, a country boasting an enormous, sophisticated arsenal of mines with a resurgent Navy holding a set of offensive Mine Warfare doctrines that are simply begging to be tested.

On the other, we have Vietnam, the Philippines and the rest of the region who are desperately “looking for a win” against the big, expansion-minded regional powerhouse. These tiny regional navies are casting about for any cost-effective means to level a playing field dominated by large numbers of aggressive Chinese combatants and encroachment by grand-scale commercial equipment–rigs, dredges and other craft.

For all parties, mines offer a pretty painless way to tactically advance their various agendas.

Now, if the South China Sea was an isolated corner of ocean, a little intramural dalliance with mine warfare might pass relatively uneventfully, but the South China Sea is one of the busiest transit-routes for Asian commercial trade, making nearby mine warfare a regional–even a global–economic threat. And believe me, when mine warfare starts in the South China Sea, it’ll make the old Iranian efforts in the Strait of Hormuz look like child’s play.

Am I being alarmist? No. As somebody who has tracked at-sea violence in this region for almost a decade, this region tolerates a far higher level of violence than the West is used to seeing. Cold War-era “fishing wars” off of Iceland–where an occasional trawler got “bumped” by a patrol boat–would provoke banner headlines on the New York Times. Until recently, whole Vietnamese fishing boats could disappear in a hail of gunfire with little-to-no notice in the American press. Folks play for keeps in China’s near seas–it’s where “dignified” western norms of behavior don’t apply.

Am I being alarmist? No. As somebody who has tracked at-sea violence in this region for almost a decade, this region tolerates a far higher level of violence than the West is used to seeing. Cold War-era “fishing wars” off of Iceland–where an occasional trawler got “bumped” by a patrol boat–would provoke banner headlines on the New York Times. Until recently, whole Vietnamese fishing boats could disappear in a hail of gunfire with little-to-no notice in the American press. Folks play for keeps in China’s near seas–it’s where “dignified” western norms of behavior don’t apply.

But that regional apatite for confrontation means things could get out of hand very, very quickly.

Mark my words.

Mine Warfare will make an appearance in the South China Sea–unless the key users of this ocean–Japan, Singapore, South Korea, etc.–start taking the threat of South China Sea escalation into mine warfare seriously. Key users need to model out the consequences of mine warfare (military, economic, environmental, political, etc.), start regularly flowing mine-clearing assets into the region and begin to demand, right now–TODAY–that key commercial transit lanes be kept clear and that freedom of navigation be maintained.

But, for these regional players who are struggling for territory, the temptation to use mines is going to grow.

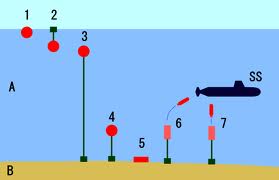

China will be increasingly eager to restrict outside access to areas full of sea features and “starve out” the small, pesky garrisons that pepper the region. Rather than take the confrontational route of chasing down and halting (or sinking) small resupply boats, China can simply declare a small area “closed”, throw mines down, offer one-way flights out to the garrisons and then sit back and watch as the Philippines and Vietnam struggle to decide how to cross into the mined areas.

China will be increasingly eager to restrict outside access to areas full of sea features and “starve out” the small, pesky garrisons that pepper the region. Rather than take the confrontational route of chasing down and halting (or sinking) small resupply boats, China can simply declare a small area “closed”, throw mines down, offer one-way flights out to the garrisons and then sit back and watch as the Philippines and Vietnam struggle to decide how to cross into the mined areas.

There’s also a real temptation to experiment. Some in the PLA(N) will likely see the South China Sea as an unparalleled “real-world” incubator for tactical innovation or as a testbed for larger mine warfare operations against future threats like Taiwan, Japan or Korea.

As an added benefit, any threat of mine warfare would be enough to temporarily usher large U.S., Japanese and other “interested” combatants/observers out of the area–so if China wanted to do something more dramatic (say, seize an island or two) without the fear of intervention/interruption by outsiders, the threat of mine warfare will be the way it’ll all start.

On the other hand, the small, hard-pressed navies of Vietnam and the Philippines would like nothing better than to force China’s large fleet to “back off” and to make Chinese agents of commercial encroachment think twice before sending large capital investments into the South China Sea (economically speaking, using a $100,000 dollar mine to disable a billion-dollar exploration rig isn’t a bad tradeoff at all). Mines are cheap, can be distributed easily, and might make China think twice about committing their new and shiny Navy to a gritty IED-ridden area.

On the other hand, the small, hard-pressed navies of Vietnam and the Philippines would like nothing better than to force China’s large fleet to “back off” and to make Chinese agents of commercial encroachment think twice before sending large capital investments into the South China Sea (economically speaking, using a $100,000 dollar mine to disable a billion-dollar exploration rig isn’t a bad tradeoff at all). Mines are cheap, can be distributed easily, and might make China think twice about committing their new and shiny Navy to a gritty IED-ridden area.

On a larger scale, the smaller countries might gamble with the innate “plausible deniability” of mine warfare, distribute mines freely, and hope that China, if it suffered a loss, would over-react and suffer disproportionate economic and political impact from that over-reaction. Internationalization of the conflict benefits the little guys–and mines are an easy–and maybe the only–way to escalate without suffering a loss.

It’s all an awfully risky game.

It’s all an awfully risky game.

And America certainly isn’t ready. The mine-hunting Littoral Combat Ship program has been thrown under the bus, and the larger mine warfare community has been so regularly sacrificed at the “Blue Water Church of Missile Defense and Aircraft Carriers”, there’s simply nothing left (Seriously–go to the local library, pull out an old ’60s–even a ’70s!!–era Janes’ and look at how many mine warfare ships and craft were in the inventory). The mine losses of the Iraq war have been ignored, and the U.S. Navy has forgotten the very real and very hard lessons learned off the coast of Korea in the ’50s. America is just not serious about mine warfare.

Now, what would be very interesting is if some of the big regional players–who both depend on free passage of the South China Sea AND are more prepared for mine warfare than the U.S.–declared that South China Sea mine warfare was an existential threat and moved unilaterally (or as a coalition) to make sure that such a step won’t happen. We’ll see.

Like it or not, mine warfare is coming to the South China Sea. And we all had better be ready, because, when it does happen, it’ll be a complex geo-political challenge that could easily cascade into a global crisis.

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

If mines ever come to play in the South China Sea, the most who will be affected is Vietnam. But for China it would be like shooting yourself in the foot also. That would restrict movement of their commercial vessels. All the Philippines has to do is to mine Balabac Strait/Palawan Passage and Bashi Channel and their vessels has no way to go but up the Japanese controlled islands. The way to ward-off China is not to confront them militarily but cripple their commercial movements, especially their 700+ ships that ply the world’s waters. But before this ever happens, South Korea, Japan and the US would definitely get involved because this will cripple their economies also.

True, but in general terms actions are within grey areas or are sufficiently ambiguous in nature by virtue of who is doing what to whom, to provide for a degree of separation between PLA and the outcome of the actions. There is nothing ambiguous about mines -especially if you declare them.

I would anticipate that mines would be more likely to be used against China by a weaker adversary who felt that they no longer had anything to lose.

Hmmm…I agree with you ChrisA…but I’d also say that a blockade is a hostile act, and I think the Philippines in particular would argue that blockades are being used to exclude access to territory and facilities that are under dispute in the South China Sea.

My concern is that the genteel rules of conduct are often disregarded in China’s near seas–it’s a rough place, and years of tough conduct out there, i think, desensitizes the public and policymakers. It’s a recipe for miscalculation.

I do also note that China has unexpectedly begun to move their large exploration rig out of contested Vietnamese waters.

Ref: International law applicable to Armed Conflicts at Sea (San Remo Manual)

I don’t disagree that mine warfare is a serious threat potentially from both state and non state actors. However it is a long bow to draw to say that competing states will pre-emptively employ mines to exclude access to territory or facilities that are under dispute.

Employing mines is not something to be entertained lightly – laying of sea mines is a hostile act. The declaration of an ADIZ on the other hand is not, neither is harassment of commercial or other government vessels by paramilitary forces.

To the best of my knowledge there is presently no war being fought by the various claimants to maritime territory in and around the SCS.

All very good points. I could see them especially using this in areas around the disputed islands that shipping vessels tend to avoid anyway. If they did it within their own claims to territorial waters and warned other nations, I could see this being no more contentious than China’s ADIZ.

It’ll be important for the U.S. to have this scenario thought through–mine warfare alone shouldn’t be the show-stopper that it is, and, well, third party conflicts that spill over into the global commons are going to be far more frequent than we like, and America historically….does about as well with those complex challenges as we do with mine-clearing. We under-resource it, fumble too often and then…stuff explodes…

Excellent points. I’m afraid you are right. The Vietnamese certainly have reason to remember the effects of the mining Haiphong.