As the Africa-centric components of the Department of Defense turn from their normal terrorist-whacking duties to engage Western Africa’s Ebola fight (a disease outbreak which, sadly, seems to have taken the Pentagon somewhat by surprise), it’s worth taking a moment to remind the Department of Defense that Liberia is the only country in recent memory whose infectious environment defeated the Marine Corps, sending an MEU home in disarray.

As the Africa-centric components of the Department of Defense turn from their normal terrorist-whacking duties to engage Western Africa’s Ebola fight (a disease outbreak which, sadly, seems to have taken the Pentagon somewhat by surprise), it’s worth taking a moment to remind the Department of Defense that Liberia is the only country in recent memory whose infectious environment defeated the Marine Corps, sending an MEU home in disarray.

That’s right. Look, Liberia is a very, very dangerous place for folks who willfully suppress the mundane aspects of every-day tropical soldiering–and forget that in past tropical conflicts, up to 75% of the casualties came from disease. And Liberia….if you’re gonna be operating there, you better be a pro or you just shouldn’t go.

Here’s what happens if you don’t take Liberia’s environment seriously. Back in 2003, some 225 Marines with the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit deployed to Liberia. They stayed for a matter of a few days, and then, well, once the Marines were safely back aboard ship, the Marines started coming down with a mysterious illness –in droves. Eighty of the deployed Marines–about 35% of the deployed force–started suffering malaria symptoms, and half of ’em became so ill that 44 were evacuated to Landstuhl Germany or Bethesda. Five suffered a complicated course of disease, requiring a stint in an intensive care ward, on ventilators. In the end, a few were medically invalidated.

So, for those of you who are unfamiliar with Marine Corps loss rates–take my word for it–this unit suffered a tremendous casualty rate. It was one of the biggest malaria outbreaks encountered by the U.S. Military since Vietnam (and the rates would have been higher had the Marines started to, essentially, self medicate (“oh, maybe I better take these pills in my kit after all”) after the outbreak became apparent.)–and if the Marines had been engaged ashore, away from the comforts of the MEU’s medical facilities (such as they were), the losses would have been far, far higher.

What bothered me back then was that the warfighters were totally unprepared. They failed to appreciate Liberia’s ferocious transmission rate, failed to take effective prevention measures, failed to detect the infection, failed to properly diagnose the infected in a timely manner…it was a disgraceful performance all around. And it was a job that should have been learned, coming, as it did, so closely on the heels of the anthrax business and the Iraq “mobile biolabs of doom” silliness.

In this 2003 case, the military’s biomedical intelligence system failed the country, and, given the slow response to Ebola today, I suspect our military’s medical intelligence arm isn’t much better today than it was in 2003. It’s not that we aren’t collecting–Sure, we may have the data someplace, but that information sure isn’t being fed up the chain in a way to get effective options to decision-makers in a timely fashion. Somewhere, somebody in the information-vetting/threat evaluation business (probably a few warfighters hired into specialized civilian roles in an intel office someplace) doesn’t appreciate medical/public health challenges.

We certainly haven’t been quick to learn any lessons about operating in Liberia’s malaria-infested environment. In 2009–just six years after the Marine Corps debacle–the Navy lost a sailor to malaria after a stint in Liberia:

Petty Officer 3rd Class Joshua Dae-Ho Carrell — a builder assigned to Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 3 — was part of a 24-person detachment that has been working on humanitarian construction projects in the capital city of Monrovia since August. His unit is based out of Port Hueneme, Calif., but was deployed to U.S. Naval Station Rota, Spain.

Carrell, 23, was transported to Landstuhl on Dec. 22 and died four days later, according to a Navy spokesperson….Navy officials did not say if Carrell had been taking the anti-malarial medication.

When are we going to learn?

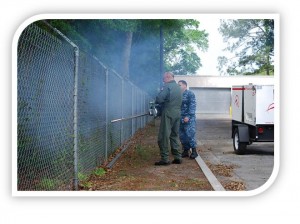

The only high-ranking guy I’ve seen recently publicly poking around in some of the dank, under-funded corners of the military’s public health infrastructure is, well, a known history buff named Admiral John C. Harvey. (Seriously, look at the photo on the right–when was the last time you saw a four-star getting first-hand experience with vector control tools?) I sure wish more high-ranking officers took such an interest.

In my mind, the biological conditions on the ground are just as important as the weather. And, while the Military spends billions on meteorological assets–since they’re, you know, key assets in direct support of the warfighter–military disease surveillance assets get routinely underfunded, lumped in some sort of odd energy-and-resource-dissipating healthcare, homeland security, support for civil authorities and intel nexus. I’ll cite an old New York Times Op-Ed:

“Although the Army has the world’s most successful malaria drug laboratory–the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research has discovered three of the five most effective drugs since World War II — the Department of Defense allocates it only $8 million a year…These sums are woefully inadequate. If a terrorist group had a weapon that would hospitalize 25 percent of American soldiers within weeks, wouldn’t the Pentagon spend more than $8 million a year to defend against it?”

The idea that the Military must focus on “Warfighting First” is valid–until knuckle-draggers use that focus to try and defund things meant to ensure the health of the deployed warfighter.

As I wrote before:

“Flesh and blood remain the central element of all weapons systems. The will and physical capability to fight remain the crucial factors in any equation for victory. If commanders are unable to recall the hard medical lessons learned in previous conflicts, and fail to ensure the health of their soldiers, how can America expect to confront bioweaponry or other, more dangerous infectious threats?”

That’s a message well worth remembering now, as the Department of Defense gets ready to engage in another dangerous environment. Even without Ebloa, Liberia can kill. So…for all you knuckle-dragging planners out there who are just starting to pour over maps of Sub-Saharan Africa, remember–Take care to understand your operational environment…or the environment will take care of you.

(**A NOTE ON COMMENTS–THE COMMENTING SYSTEM IS BROKEN–YOU CAN SUBMIT COMMENTS AND I SEE YOUR COMMENTS, BUT THEY AREN’T BEING POSTED TO THE BLOG**)

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this subject, Craig. I thought you might.

In a recent email to you I ranged much farther afield concerning the US response to the current Ebola epidemic. There is cause for doing so. But I can appreciate your decision not to follow me. You have a job. I do not. And Dr. Laurie Garrett seems to be far out in front of everyone on this subject, any way. There is nothing that can gainsay what she has said.

Still, as a follow on, you might assess the readiness of the Navy to take on the mission of fighting an infectious disease. For instance, the readiness of the USS Comfort. If Ebola becomes a national security threat – and some say it already is – and the order were given to stop it at all costs, how well equipped and prepared would the Navy be to undertake such a mission ? Could the Bataan and similar vessels serve a useful purpose ??

R/s, TPH

test