It is time to face the facts: A steadily gentrifying West Coast could sink the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet far faster than any hostile Asian Navy.

It is time to face the facts: A steadily gentrifying West Coast could sink the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet far faster than any hostile Asian Navy.

It’s a maritime fact of life: To function, all navies need waterfront property and a strong, somewhat heavy industrial base to support it.

For the U.S. Navy, basing choices are delimited by deep-draft pier access, ready support from a low-cost labor pool and nearby high-tech resources. On the West Coast, where the Navy intends to pivot, viable deep-draft space for naval bases has always been in relatively short supply. Places where both a base and heavy industry can easily and economically co-locate are even rarer.

And as the West Coast gentrifies, the pro-base case gets harder and harder for locals to make.

In the past, the ancillary benefits of a naval base–strong employment, national security and services–outweighed the pollution, noise, traffic and other negatives that go with the military maritime-industrial complex. And even then, when those impacts proved to be too significant to allow peaceful co-existence, there’s usually been enough suitable space available elsewhere to relocate the base and it’s industrial support. But times are changing, and America’s Western coastline is more crowded…and more valuable than ever before.

The Navy has been playing into this trend, shedding irreplaceable waterfront assets (i.e. everything in San Francisco Bay) and consolidating their West Coast footprint down to two Superbases–Superbase San Diego and Superbase Bangor-Kitsap-Everett.

Those massive, multi-component bases were originally supposed to be too powerful to dislodge, and too integral to their resident communities to challenge–or so the economics-minded and efficiency-seeking base consolidators thought.

But now, they’re just huge economic targets of opportunity.

In San Diego, the threat-of-the-day is residential encroachment–in the guise of what is known as the Barrio Logan Community Plan.

In San Diego, the threat-of-the-day is residential encroachment–in the guise of what is known as the Barrio Logan Community Plan.

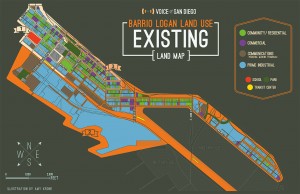

For those who don’t know San Diego, Barrio Logan is the low-income, mixed-use residential-ish neighborhood that has, for years, co-existed in the rough buffer between downtown San Diego, the yards and the Navy base. The neighborhood has–to it’s credit–been long ignored, and, to fix that, the neighborhood assembled a long-term development plan to get the community’s needs on the table.

That’s all well and good, but the neighborhood got a little too interested in using the plan to boost local property values–I’ve read the draft report, and to, me, that seems like a major goal (a good summary of the competing visions is here). And that–an effort to fully realize profits from investing in this originally low-demand area–sets the stage for running shipbuilding and ship maintenance out of town. Despite protests to the contrary, I honestly suspect the Barrio Logan Community Plan is the first step in a process that will marginalize and shutter the thriving industrial waterfront that has sprung up next to the naval base–if not the base itself.

Of all the encroachment threats out there, the Navy and their industry partners need to take this challenge very, very seriously. Industry certainly recognizes the seriousness of this local fight, and is setting the stage to contest the Barrio Logan Plan in a nasty, divisive city-wide ballot. And while the Navy’s industry partners may well win this round, the the plan will come back again and again…and be harder to defeat each time.

Of all the encroachment threats out there, the Navy and their industry partners need to take this challenge very, very seriously. Industry certainly recognizes the seriousness of this local fight, and is setting the stage to contest the Barrio Logan Plan in a nasty, divisive city-wide ballot. And while the Navy’s industry partners may well win this round, the the plan will come back again and again…and be harder to defeat each time.

For me, after observing similar efforts in the Bay Area, it is easy to see how this will play out. The neighborhood, even if it has initially failed to constrain industry growth by placing a solid residential-use-only zone “fence” around the shipyards, will immediately start grousing about a host of environmental concerns (exhaust, noise, traffic, etc), that, in turn, will further constrain industrial activities on the waterfront.

Sadly, the Navy (and industry)–happy about their win in the city-wide vote–will probably dismiss much of it, given that the complaining will be done in the name of “environmental justice” by the usual “Pesky Neighborhood Organizer/Environmental Activist”. But, sometimes, those “simple folks” reflect some deep-pocketed and far less sentimental stakeholders.

There are plenty of powerful San Diego interests and real estate investors who would far rather see valuable San Diego waterfront converted into something more high-end than dirty, old-school, industrial and Navy base infrastructure. I mean, NASSCO is, remarkably, just a quick walk away from the central entertainment/convention center of town–and while the San Diego shipbuilding industry may have the heft to oppose the Barrio Logan Plan now, it’ll eventually run up against local power-brokers–all eager for San Diego to shed it’s “Navy Town” image and become home to the next wave of Silicon Valley expats–and lose badly. The best–if not only–long-term policy is to be proactive, and work to be an excellent, irreproachable neighbor.

If the Navy and Industry aren’t savvy and proactive, in time, Barrio Logan’s neighborhood demands/concerns will totally upend activities at the Navy’s SuperBase in San Diego, impacting the General Dynamics/NASSCO shipyard and all the maintenance yards there. If something doesn’t change on the waterfront, the writing is on the wall–in thirty years, that thriving, ideally-placed piece of industrial waterfront will be little more than San Diego’s next hot new residential district, where nifty, new high-tech workers sip latte in a recently-abandoned, quickly forgotten naval shipyard.

So what’s the Navy to do? Well, first–as I have argued for years–the Navy must do a better job of monitoring and responding to complex encroachment threats. Those warnings have largely fallen of deaf ears, with most rank-and-file dismissing encroachment as a tool “fringy enviro” interest groups use to limit use of training areas, stop sonar use, and limit high speed transits.

So what’s the Navy to do? Well, first–as I have argued for years–the Navy must do a better job of monitoring and responding to complex encroachment threats. Those warnings have largely fallen of deaf ears, with most rank-and-file dismissing encroachment as a tool “fringy enviro” interest groups use to limit use of training areas, stop sonar use, and limit high speed transits.

That’s not the case.

In reality, the biggest encroachment threats come from big-business stakeholders eager to appropriate bases for their own interests. Heck, I’ve watched as promoters of the natural gas trade worked to gain access to key testing areas of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, test and trial areas off Florida, Point Mugu and even Camp Pendleton–and the hits just keep coming. And while modifying training activities to better account for some endangered snail might be an annoying immediate impact to the rank-and-file, the limitations imposed by industrial or residential encroachment are far more substantive an impact than most sailors realize. The Navy must internalize this lesson and respond accordingly.

In San Diego, land and residential developers make for a powerful economic interest group. The Navy (and their economic partners) need to make their peace with this fact, and get to planning on how to better manage this local challenge.

Here’s some other suggestions on how to handle complex encroachment threats:

Here’s some other suggestions on how to handle complex encroachment threats:

First, develop a local political/business relations team to monitor and evaluate all-hazards encroachment threats-and then maintain it. Forever. And while it may not be–as the SECNAV said in a recent interview–“appropriate to take sides“, the Navy must, at least, be engaged enough in any potential encroachment-generating political processes to have a distinct position and be able to spell out for local leaders the real costs of base encroachment.

I mean–What good is a regional Superbase if the Navy isn’t going to leverage the political power and influence that comes with it?

Second, the Navy should be on the lookout for existing West Coast sources for industrial support and basing–and support development of new ones (new shipyards, new maintenance facilities, new suppliers). It might be wise to leverage facilities up north for more flexible basing and maintenance options up in Puget Sound, Los Angeles or even (gulp!) San Francisco. Such redundancy is a wise move anyway, particularly given the West Coast’s ugly predilection to periodically shake certain portions of itself into rubble. But alternatives gives the Navy–at a minimum–a better position to negotiate a favorable outcome.

Third–and probably most importantly– is that the Navy needs to start taking Green Fleet operations seriously. Those Green innovations can be very helpful in demonstrating the Navy is a good neighbor (It’s one of those neat ancillary benefits of being serious about Energy Security), and that’s critical as more and more people expect to make large investments and enjoy a high quality of life next to working naval facilities.

Third–and probably most importantly– is that the Navy needs to start taking Green Fleet operations seriously. Those Green innovations can be very helpful in demonstrating the Navy is a good neighbor (It’s one of those neat ancillary benefits of being serious about Energy Security), and that’s critical as more and more people expect to make large investments and enjoy a high quality of life next to working naval facilities.

Reducing the Navy (and the naval industrial base’s) local environmental impacts (in a creative, cheap and quantitative fashion) is critical to being a good neighbor. It can solve issues before they become costly, divisive issues.

If nothing has been done by the time Barrio Logan’s large cadre of politically active asthmatic citizens start another round of complaining about their industrial neighbors, and naval leaders are unable to show San Diego’s leadership a quick, simple and definitive powerpoint on how the naval waterfront has used green tech (and other base resources) to reduce local emissions, lowered crime and saved the odd kitten or two, then the Navy has lost the battle.

If motivated by a good encroachment management team, the Navy can do a lot in terms of measuring conditions, gathering data and helping define favorable environmental measures–and use that to get out ahead of local rabble-rousers.

I’m not kidding. The Navy and it’s industrial friends must be able to prove that they are good neighbors on a very visceral level–simply charting out the number of jobs created/sustained won’t cut it (not when Silicon Valley is a quick road trip away). If it means General Dynamics Shipbuilding King Fred Harris and SECNAV Ray Mabus need to go and occasionally tend Barrio Logan crosswalks, distribute saplings to locals, and fund mural-painting contests, so be it–it’s just that the Navy must be able to demonstrate that they (and their industrial allies) are great neighbors.

Done right, everybody wins.

(And if industry still wants to get aggressive, it might also help to educate the locals on what gentrification means for them–if they don’t own their homes, they’ll be priced out, the demographic background of the neighborhood will change, old jobs will go and be replaced with low-paying service jobs and so on…)

But time is short–If the San Diego’s naval waterfront doesn’t have a strong, eminently PR-worthy “Green” record to leverage in demonstrating that they are good neighbors in the local community, then it is high time to start building one.